Dancing in her grandfather’s footsteps

Raelene Whiteshield champions financial education while changing the world one ribbon skirt at a time

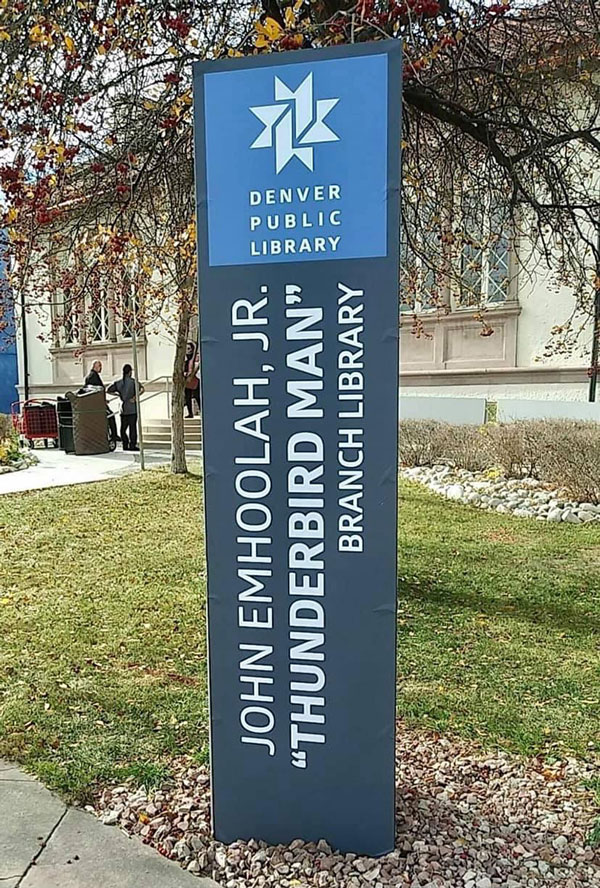

Inspirational, dedicated, tireless: Those are some of the words that have been used to describe the late John "Thunderbird Man" Emhoolah Jr., a longtime advocate for Native American education across the United States.

Among a long list of achievements, Emhoolah created the Native American Studies program at the University of Washington, co-founded and served as the first chairman for the United Tribes Indian Foundation, and successfully lobbied for the funding of tribal colleges through his work with the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

Those are some big shoes to fill. But today, Emhoolah's granddaughter, Raelene Whiteshield, known as Tsa-Geah-Hodle-Mah in the Kiowa language, is carving her own path by working to bring native traditions, such as the sewing of ribbon skirts, to Denver-area Native Americans whose families may have lost them. Meanwhile, as a commercial banking client relationship specialist at BOK Financial®, she's forging ahead in an industry that has historically been disconnected from Native Americans.

The disparity is quite dramatic. More than 16% of American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) households do not use a bank or credit union for financial transactions, a higher rate of "unbanking" than any other minority group, according to a 2019 FDIC survey. These groups have lower rates of financial literacy than whites, Asian Americans and Blacks, according to research published by the Social Security Office of Retirement and Disability Policy.

Financial institutions like BOK Financial are working to build better relationships with Indigenous communities. BOKF has served Native American tribes for more than 20 years, now with a total of more than 45 tribal relationships across the U.S.

However, to truly bridge the gap, the financial services industry has to reach out to Native Americans from a young age, according to Whiteshield. "It would be beneficial if a lot more financial institutions came in and helped introduce 'basic 101' finances like checking accounts, how you obtain credit, how you maintain your credit and homeownership," she said. That outreach would not only build financial literacy but also help Native Americans have more confidence in banks, she explained. "There's a little bit of a trust issue."

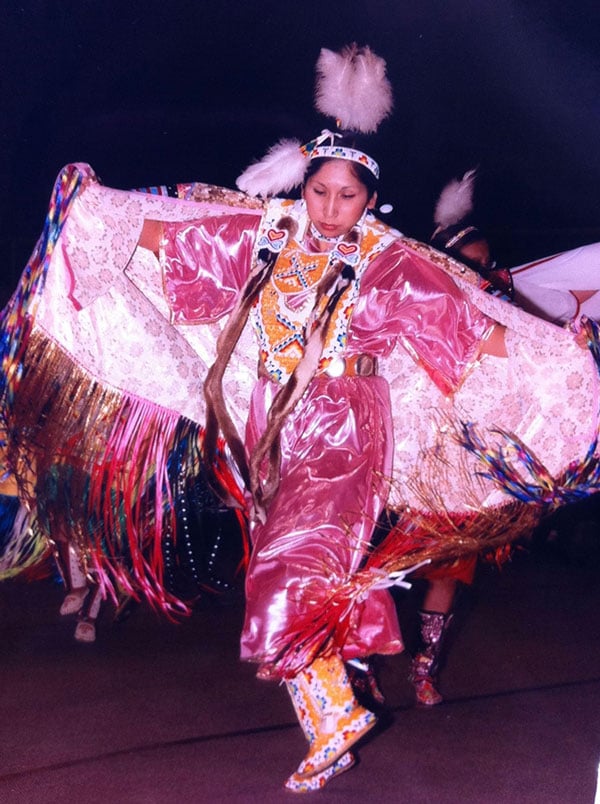

Champion dancer

If you ask Whiteshield's family to describe her, one of the first things they'll mention is her dancing.

Her brother, Raymond Eagleboy Whiteshield, recalls favorite childhood memories of their travels through the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana during the summer, when they would dance together at weekend powwows.

Her mother, Deb Emhoolah, also fondly remembers taking her to ceremonial events as soon as she could walk. For young Raelene, competing at these dance contests—whether as a child or even today as a champion dancer—is not just about competition but about community.

"You just go and dance and have fellowship. You get to meet people and talk to people from many walks of life," she said.

That sense of community has been healing throughout her life. "Growing up in a world where the kids did not look like you, that was hard," she recalled. At the same time, her home life was full of rich traditions that she didn't realize were part of Kiowa tribal culture until she got older: her grandfather's stories and her family's travels across North America to powwows, where she competed in dance competitions.

Raelene Whiteshield and son Wades-In-The-Water Running Wolf (13) at the Denver Public Library branch event. They are dressed in traditional Kiowa Gourd Clan Tiah-Piah Society attire.

Although these traditions made her family different from the other families at school, they connected her family to the larger tribal community and are still a source of pride today. In fact, one of the lessons that she has taught her four children since they were young is to avoid measuring themselves against Anglo-American culture.

"I taught them don't view yourself on a Westernized standard—because we're not that," she said.

Meanwhile, since the early 2000s, Whiteshield has worked on projects within the Denver-area Native American community with longtime family friend Donna Chrisjohn, who is a former co-chair of the Denver American Indian Commission and now serves as a commissioner.

Their latest endeavor is a Ribbon Skirt Collective —through which they provide "ribbon skirts," brightly colored clothing traditionally worn by American Indian women, for Indigenous families that need them for ceremonial and celebratory events.

Previously, Whiteshield worked on her own to make the skirts, sewing more than 200 and often paying the costs for materials out of pocket. (Chrisjohn calls Whiteshield "an incredible seamstress.") Through the collective, the two women provide either the skirts themselves or kits for families to make them.

An unlikely path

Deb Emhoolah also introduced her daughter to a world beyond their rich culture as members of the Cheyenne, Arapaho and Kiowa Tribes of Oklahoma. Whiteshield's career in banking began nearly two decades ago at Native American Bank in Browning, Mont., where she worked her way up after beginning as a teller. Her mother, now CFO of the Delaware Tribe of Oklahoma, worked at Native American Bank for 20 years.

But the two women's careers are certainly not the norm among Native Americans. Only 0.4% of professionals working in banking and credit are American Indian women, according to a U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission special report.

It's a statistic that Deb Emhoolah has experienced firsthand. She recalls it being difficult to find tribal members who had experience in banking when she started at Native American Bank in 2002.

This relationship between banks and Native American communities is important because, as Emhoolah notes, access to capital is necessary for the economic development of these communities.

Meanwhile, the key to creating more financial literacy among Native Americans is education, starting as early as K-12, according to Whiteshield. She and Chrisjohn have worked together on educational projects that teach about Indigenous culture, and she hopes that the financial services community will work to teach Native American children about finances.

Kind and big-hearted

Not long ago, the Denver Public Library honored John Emhoolah Jr. by renaming a branch after him.

But for Whiteshield, what will always stand out about her grandfather is less about what he accomplished and more about how he treated others.

"My grandpa was very selfless. He had so many friends from across the whole U.S. and Canada, and he was just always really nice," Whiteshield said. "He was always open. I try to be more like that—really easy-going and selfless."

She jokes that she would like to accomplish "at least one thing," compared to her grandfather's long list of accomplishments. Chrisjohn offers a different view.

"I think Raelene is one of the funniest, most clever and sharp-witted individuals I've ever met," she said. "She's also just big-hearted and kind to everyone."

It's a sentiment her grandfather, himself a champion for learning, would certainly have agreed with.

Top photo caption: Daisy Eagle Speaker, Joslyn Running Wolf, Rhiannon Eagle Speaker, Crystal White Shield, Cheryl Cozad and Raelene Whiteshield performing the Ton-Kon-Gah Kiowa Black Leggins Warrior Society Dances Scalp and Victory Dance in honor of veterans during the Denver Public Library branch renaming to the John Emhoolah Jr. Library.