Why is my grocery bill so expensive?

Food inflation hitting lower income people the hardest both here and abroad

It's not just your perception: Everything at the grocery store did become more expensive.

In fact, food prices were up 8.8% in March, compared to one year ago, according to Labor Department data. And it's not just in grocery stores where consumers are feeling the pinch: The price of food eaten away from home, such as menu options at restaurants, bars and cafeterias, rose 6.9% from March 2021 to March 2022.

Although the current food inflation rate was in line with expert expectations, the question going forward is whether that figure will go higher or lower over the next few months, said Steve Wyett, chief investment strategist for BOK Financial®. "Food prices have been volatile in the past, and we're in a period of high volatility right now."

What's impacting the prices?

One of the primary factors exacerbating food inflation is the war between Russia and Ukraine, experts said. "Ukraine and Russia are big exporters of basic food commodities like wheat and corn. Plus, Russia is one of the world's largest exporters of fertilizer potassium, or 'potash,' that's used in crops," said Brian Henderson, chief investment officer at BOK Financial. "Ukraine is getting pretty close to planting season and, if the invasion goes on, it will reduce the supply of crops that Ukraine farmers are able to produce."

Spring fieldwork there traditionally starts in late February or March but has been delayed by cold weather this year. The APK-Inform agriculture consultancy estimates that the area sown with Ukraine's 2022 spring grain crops could decline by 39% to 4.7 million hectares because of Russia's invasion.

Meanwhile, domestic factors are contributing to food inflation as well, Henderson said. For instance, COVID-19 curtailed the movement of migrant workers into Texas and California, which has impacted crop harvesting. "That's exacerbated food price inflation more recently, and it's not going down anytime soon," he said.

And to top it off, there's an avian bird flu infecting some U.S. poultry flocks, which may raise chicken prices.

Nevertheless, there are some factors that could bring food prices down as well. "Commodities have always been cyclical," Wyett explained. "If one crop isn't great, there are other markets that could benefit. They could increase production in Brazil or here in the United States to make up for the shortage. If commodity prices are high, the farmers will plant more acres in those commodities generating more supply, which would bring prices down."

Impact of higher food prices at home and abroad

In the meantime, U.S. consumers in the bottom 50% of earners are feeling the impact of increased food costs—on top of gasoline prices, which increased by 48% from March 2021 to 2022—the most because they spend higher percentages of their income on these items, Wyett said. In response to the increased costs of basic needs, lower-income consumers are already having to cut back on discretionary spending, such as dining out and monthly subscription services.

Meanwhile, those consumers who haven't already reviewed the line items in their household budgets likely will want to do so, Wyett added. "For most all of us, inflation will lead you to make sure you're spending money where you want to spend it."

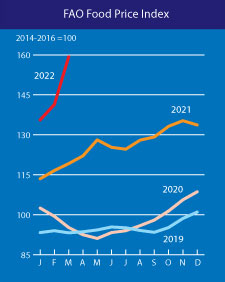

Globally, food prices are soaring as well, which is also hitting poorer people the hardest. In March, the FAO Food Price Index (FFPI), which measures the international prices of a "basket" of food commodities, including cereals and meat, averaged at 159.3 points, the highest level since the index's inception in 1990. That's also a 12.6% increase from February, reflecting new all-time high prices for vegetable oils, cereals and meat, and increases in the prices of sugar and dairy products.

Although a famine is very unlikely, there could be social unrest in countries where food costs take up a large part of people's incomes, Wyett said. For instance, high bread prices were a catalyst for the Arab Spring anti-government protests in the early 2010s. And food prices are already higher now than they were then, he noted.

Worldwide, there are nine countries where people spend more than 40% of their household incomes on food, including Nigeria (56.4%), Kenya (46.7%), Cameroon (45.6%) and Kazakhstan (43%). By contrast, Americans spend an average of only 6.4% of their household incomes on food.

In Wyett's words: "With over 1 billion people on this earth paying more than 40% of their incomes on food, this is a worrying scenario globally."