How much will the U.S. economy have to slow to combat inflation?

What we can expect for the economy through the rest of 2022

We went into 2022 expecting economic growth to be slower than what the U.S. had experienced in 2021—but still positive. After all, the job market was strong and looked to remain that way, higher-income consumers had built up wealth and savings during the COVID-19 pandemic, restaurants and other services were poised to reopen further, and there was hope that some relief for lower-income consumers would be extended through the Biden Administration’s proposed Build Back Better Plan.

Then, just two months into the year, Russia invaded Ukraine—the fallout of which has impacted food and energy prices globally. The U.S. and NATO members responded in a rapid and unified manner, imposing sanctions not just on Russian banks but also on Russian oligarchs. Several months later, no resolution between Russia and Ukraine is in sight. Meanwhile, the European Union plans to phase out its reliance on Russian oil by the end of the year, which could cause a severe economic slowdown in Western Europe. Closer to home, U.S. consumers, who were already contending with inflation before the invasion, have been hit with even higher food and energy prices.

And Russia’s invasion wasn’t the only surprise during the first half of the year. China also has extended its zero-COVID policy, which requires cities to impose strict lockdowns even if only a handful of cases are reported. The extension of this policy has exacerbated supply chain issues and, in turn, domestic inflation. Auto manufacturers have had to cut production schedules again, while new car inventories are still very low.

U.S. companies likely double-ordered goods from overseas in the first half of the year so they would have things to sell in case supply chain issues persist, which they likely will. The New York Fed’s new Global Supply Chain Pressure Index shows minimal improvement since the start of the year and anticipates that heightened geopolitical tensions will fuel supply chain pressures in the near future.

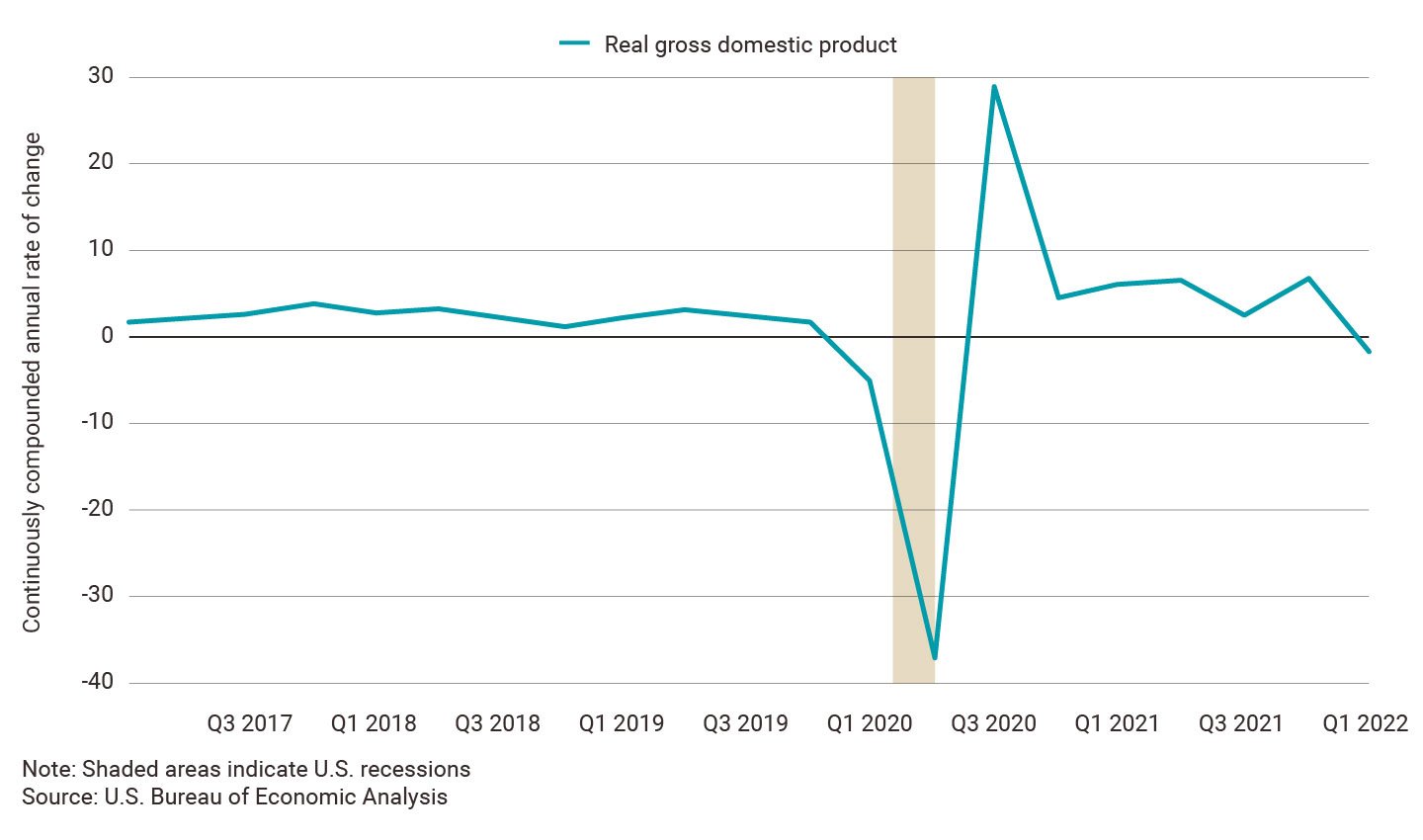

This influx of imports into the United States during the first half of the year was a huge drag on the country’s overall economic growth. From March to April alone, the international trade deficit increased by 15.9%. Altogether, real gross domestic product (GDP) actually shrank at an annual rate of 1.5% in the first quarter. That decline is despite strong consumer spending, particularly for services. At the beginning of the year, large portions of the U.S. were still in COVID lockdown that held consumer spending back. However, as these lockdowns have been lifted, there has been a surge in demand for restaurants, entertainment and travel.

Although consumer spending and the persistently strong job market likely will continue to support economic growth through the remainder of the year, I still see some potential headwinds. Overall, personal incomes have been rising with the strong job market, but inflation is taking a big bite out of consumers’ paychecks. Higher-earning consumers still have excess savings and investment wealth they built up during the last few years’ market gains. However, the rising cost of food, gas, and rent is forcing lower-earning consumers to cut back their spending on non-essentials, which in turn is dampening the earnings of companies such as Walmart and Amazon. Retailers have already been contending with higher shipping costs from record diesel prices, higher labor costs and ongoing supply chain issues. These pressures could result in layoffs and hiring freezes if sales aren’t strong for the remainder of the year.

So what does all this mean for economic growth and inflation going forward through the rest of 2022? The Federal Reserve will have to continue to hike rates in order to get core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) inflation down to their 2% target. Meanwhile, the odds for a recession this year have increased but it’s more likely to happen in 2023, after a lag.

How this impacts consumers will depend on their wealth and income level. Wealthy and/or high-income Americans likely will continue to spend more on services and travel, even as the cost of plane tickets climbs. Lower-income consumers, meanwhile, are having to put more purchases on credit cards as they grapple with higher costs. Fortunately, many consumers have paid down their balances since the 2008 financial crisis, so the climbing levels of consumer debt that we’re seeing so far this year aren’t as much of a warning sign as they were before 2008.

That said, if inflation continues to rise, the price of durable goods like appliances and cars doesn’t drop, or the large gap between labor demand and the number of workers persists, the Fed may have to do more or larger rate hikes and throw us in a recession sooner. It’s a narrow opening for the Fed to thread.

2022 Midyear Market Outlook

Join BOK Financial investment experts Brian Henderson, Steve Wyett and Cavanal Hill Investment Management President Matt Stephani for their outlook on the domestic and global economy, inflation, and the markets.