Gaining clarity on the housing market ‘mess’

Dysfunction on both the supply and demand sides of the equation underscore the disarray

If the housing market has you frustrated and baffled, you're not alone.

With the average home sales price topping $570,000 in the first quarter—21% higher than a year ago—finding a residence that fits your budget can be incredibly challenging and maddening, especially for lower-priced homes.

And yet, despite the steady climb in home prices over the last decade—the average sales price was $278,000 in early 2012—new home builders have been slow to ramp up production since the end of the Great Financial Crisis in 2009.

Taken in context with the population increase of 18 million between 2012-21 and the pandemic-driven push from cities to the suburbs, the U.S. housing supply is about 3 to 4 million units short of where it should be, said Christopher Maloney, a mortgage strategist with BOK Financial Capital Markets.

"Prices are telling us the housing sector is a mess," said Maloney, who actively monitors U.S. housing activity to anticipate its impact on the mortgage-backed securities market. "Rising prices are not a sign of a booming housing market, but a sign of a desperate shortage of inventory due to a lack of building and years of a depreciating U.S. dollar.

"I would argue that the housing sector was not a so-called 'bright spot' over the past few years, but quite the opposite."

Stark shortages

In addition to fulfilling a core human need for shelter, the housing market is an important part of the broader U.S. economy, accounting for nearly 18% of the nation's gross domestic product in 2020. About 23% of that slice of the nation's economic pie was tied to the building of 1 million new housing units and activity in the remodeling industry.

In 2021, 1.1 million residences were newly built and there were 6.1 million sales of existing homes, which accounted for 90% of total real estate sales, according to the National Association of Realtors. Nonetheless, the U.S. rate of home ownership, which touched a one-decade high of 67.9% in mid-2020, slipped to 65.4% in early 2022.

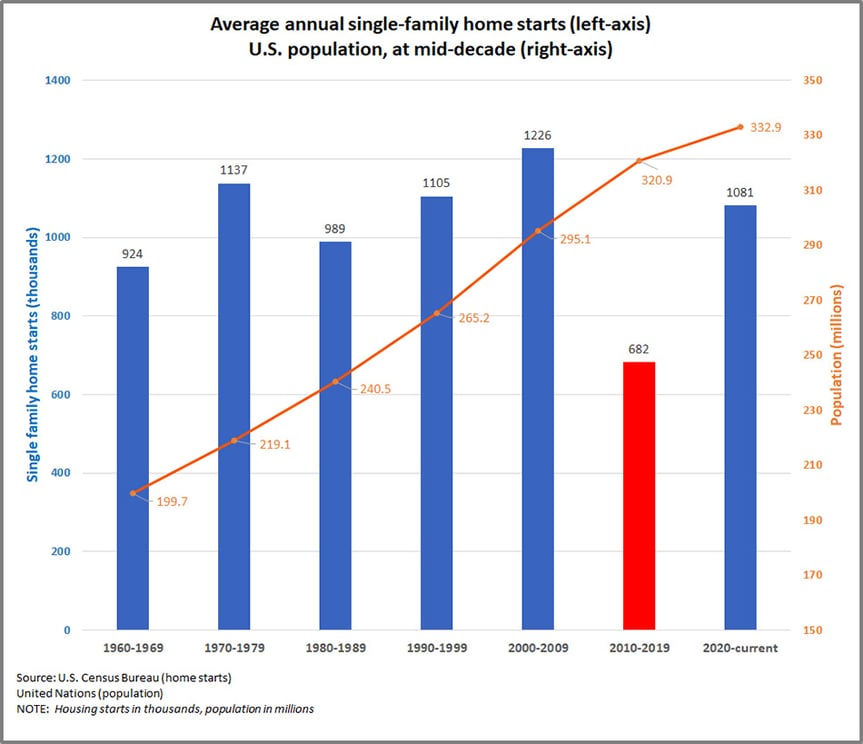

Maloney said the supply side of the equation factors heavily in the current disconnect. His research found that new home construction or "starts" lagged population growth significantly between 2010-19, which ended with the lowest average production since the 1950s. Exacerbating matters have been state and local rules and regulations that dissuade new building.

"There is no economic reason that homebuilders have stopped meeting housing demand over the past decade-plus—when you see modest homes in certain locales such as San Jose, California, going for over $1 million, that should cause every homebuilder to pack up and head there, but they're not," he said. "I believe at root this is a political problem related to local regulations, taxes, fees and 'not in my backyard' resistance that skews the natural regulator of supply and demand."

Demand cooling

In May, the number of new home starts declined on both a month-over-month and year-over-year basis as homebuilders contended with continued supply chain issues, increased borrowing costs and reduced confidence in the broader economic outlook. Existing home sales also dropped to an annual rate equivalent of 5.4 million units, although existing home inventory was lower than a year earlier.

While offering no relief on the supply challenges, the recent data did reflect softening demand as many homebuyers experienced sticker shock with 30-year mortgage rates averaging 5.70% at the end of June—up significantly from 2.98% a year earlier.

The sub-3% home loan rates accessible for much of 2020 and 2021 reflected the abundance of cash that flowed into the economy from the Federal Reserve's easy money policies and congressional spending on pandemic relief and other domestic programs. Yet, lower rates created the unusual dynamic of fueling steadily higher housing market demand despite the surging prices.

Although he anticipates the mortgage-rate jump may create pressure on the Federal Reserve to stop its current monetary tightening, Maloney believes the path back to housing market normalcy will require near-term pain.

"The more sustainable solution to the current housing crisis is not ever-cheaper credit," he said. "What lawmakers need to do is determine how to create more supply, which will lower prices and increase demand organically."

A crash unlikely

Despite the subdued outlook for homeowners, Maloney is confident the U.S. housing market won't experience a full-on collapse as it did following the Great Financial Crisis, although select overheated markets may endure sharper declines than others.

He said that relatively solid credit profiles among borrowers should buffer lenders' loan portfolios from defaults while institutional buyers of single family homes are heavily invested in keeping prices at healthy levels.

"I'm not sure how the business model of landlords owning a number of single-family homes scattered across a city is as efficient as owning an apartment building where all of your tenants are in one building, but time will tell on how that works out," he said of the rise of institutional home ownership.

The key to ending the affordability crisis, Maloney added, is letting the market once again determine prices, and not just in the mortgage market.

"Prices have an information content that tells buyers what's scarce and what's plentiful and tells sellers what buyers want and don't want," Maloney explained. "If you start messing with prices—and interest rates are a price—it means you're flying blind because you destroy that information content.

"You have to leave prices alone."