How will quantitative tightening affect the economy?

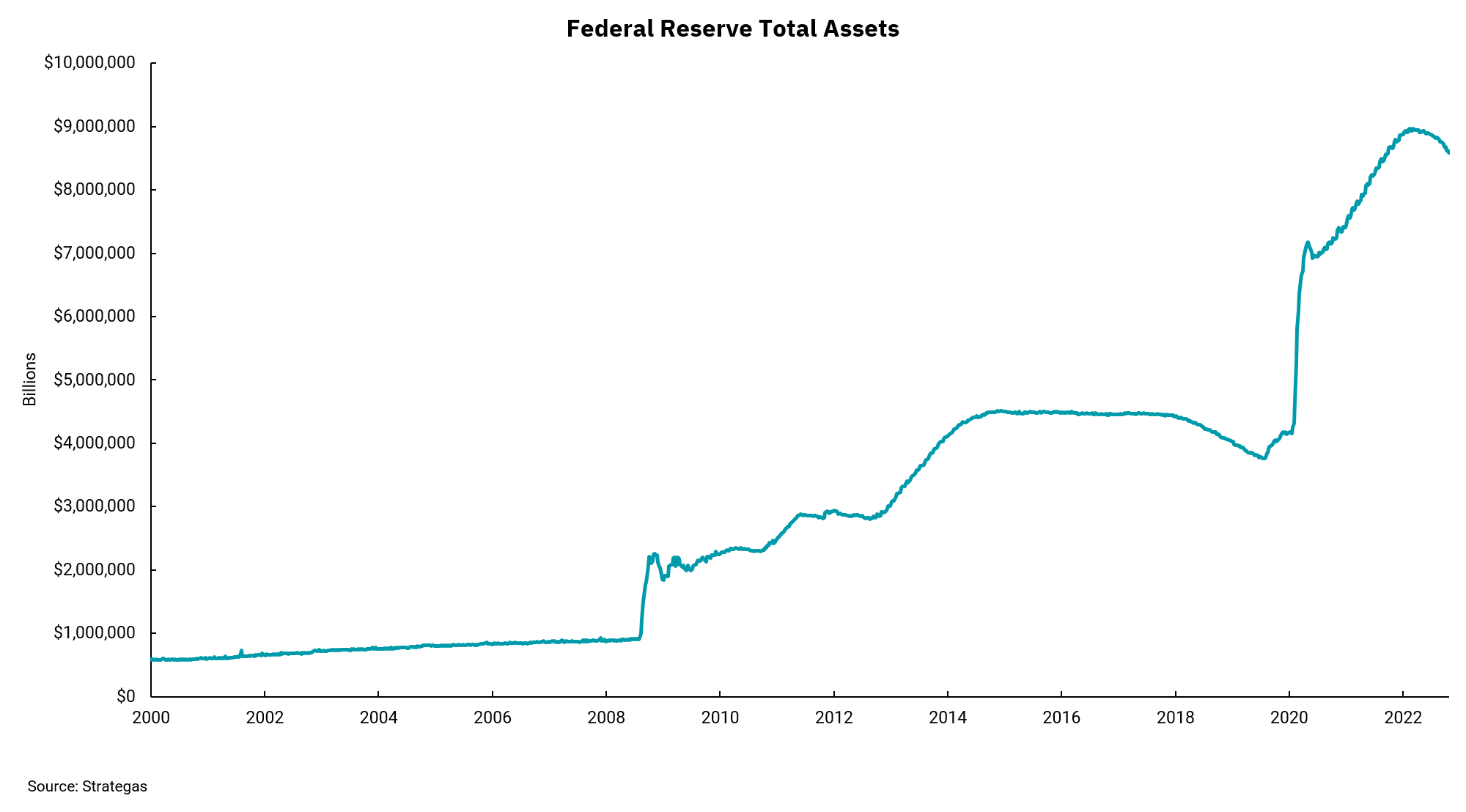

Questions remain as the Fed shrinks its near-$9 trillion balance sheet to combat inflation.

The Federal Reserve rate-setting arm, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), is scheduled to meet Dec. 13 and 14. So far, they have voted to raise rates at every meeting this year, starting at 0.25% but quickly accelerating to 0.50% and then 0.75% at each of the last four meetings. This month we expect them to slow the tightening back to 0.50%, bringing the fed funds to a target range of 4.25- 4.50%—all in all, an extraordinary year of rate increases. We also expect another 0.50-1.00% in hikes during the first quarter of 2023.

The use of interest rates to influence economic activity is a commonly used tool for central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve. But beginning with the financial crisis in the early 2000s, the U.S. Fed started to utilize its balance sheet as another tool. Increasing the balance sheet's size by buying securities, primarily treasury securities and government-guaranteed, mortgage-backed securities, could help reduce interest rates and spur economic demand. This week's chart shows this process beginning in 2009 with a sharp increase and then gradually growing until 2018, when the first attempt to reduce the size of the balance sheet occurred. The Fed had already reversed course on this balance sheet decline when the global pandemic hit, and the Fed then significantly increased the size of the balance sheet.

After topping out near $9 trillion, the Fed has now begun another process of reducing the size of the balance sheet. It has been hard to quantify how much growing the balance sheet helped, which means it is hard to know how much shrinking the balance sheet will hurt. But if we take it as a given that raising the size of the balance sheet helped the economy grow, then shrinking the balance sheet will be a headwind to growth going forward.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)