Bond forecast: Smoother sailing ahead

After a dismal 2022, fixed-income investments are positioned to reclaim traditional portfolio role in 2023

The U.S. bond market is poised for a return to normalcy in 2023.

Of course, given the harrowing abnormality of 2022, even the smallest dose of sanity will be cheered by investors of all sizes.

“For all the pain we’ve gone through this year, we feel better about the bond market moving forward than we have in a long time,” said Steve Wyett, chief investment strategist for BOK Financial®. “We can once again actually look at bonds the way they’re supposed to be used within an investment portfolio, that is to generate cash flows and provide a cushion to stock market volatility.”

Therefore, Wyett sees bond yields, which soared in 2022 and contributed to generally the worst returns in decades for such investments, likely remaining within a range in the coming year that better reflects the related risks.

“It doesn’t mitigate the pain we’ve been through in 2022, but having gotten through that pain, bonds look a lot better now,” he said.

Losses for the ages

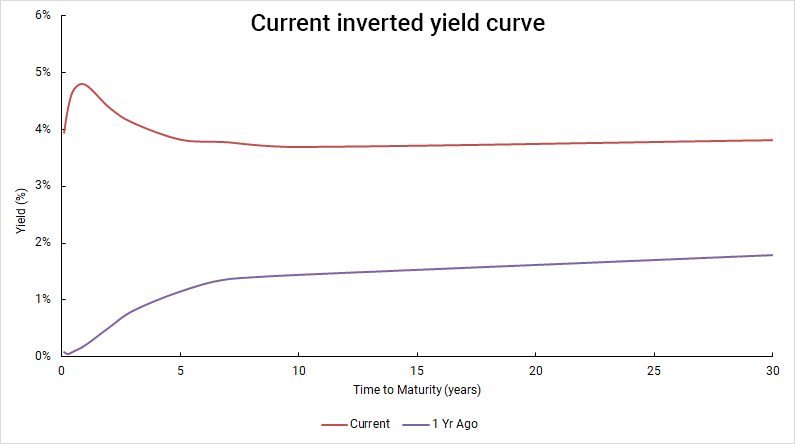

As financial markets rang in 2022, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s key overnight lending rate was essentially 0% and the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds was 1.52%. As of mid-December, the Fed’s overnight rate was set at a range of 4.25% to 4.5% and the 10-year Treasury was yielding in the vicinity of 3.5%.

The sharp changes wreaked havoc upon the bond market. As of mid-November, traditionally stable short-term bonds that mature within three years had lost an average of about 4%, intermediate-term bonds that mature between three and 10 years averaged around an 8% setback, and long-term bonds that mature in 10 years or beyond sustained an average decline of more than 30%.

“Experiencing stock-like losses in the bond market is so outside the realm of what we normally expect,” Wyett said. “But it was totally driven by the math of how low rates were at the beginning of the year and how aggressively they needed to rise as the Fed began to combat inflation.”

The underlying culprit was inflation. Price gains hovered at four-decade highs for much of the year, fueled by resurgent consumer demand, supply chain issues that persisted through much of the summer and excess cash in the system due to abundant pandemic-era fiscal spending as well as the Fed’s near-zero lending rate.

Amid such conditions, bond prices largely dropped to push yields, which move in the opposite direction, closer to the inflation rate. The 2022 bloodbath afflicted the vast majority of bond types, from corporate bonds issued by high quality companies and riskier ventures alike to debt issued by federal, state, and municipal governments and agencies.

Unknowns still lurking

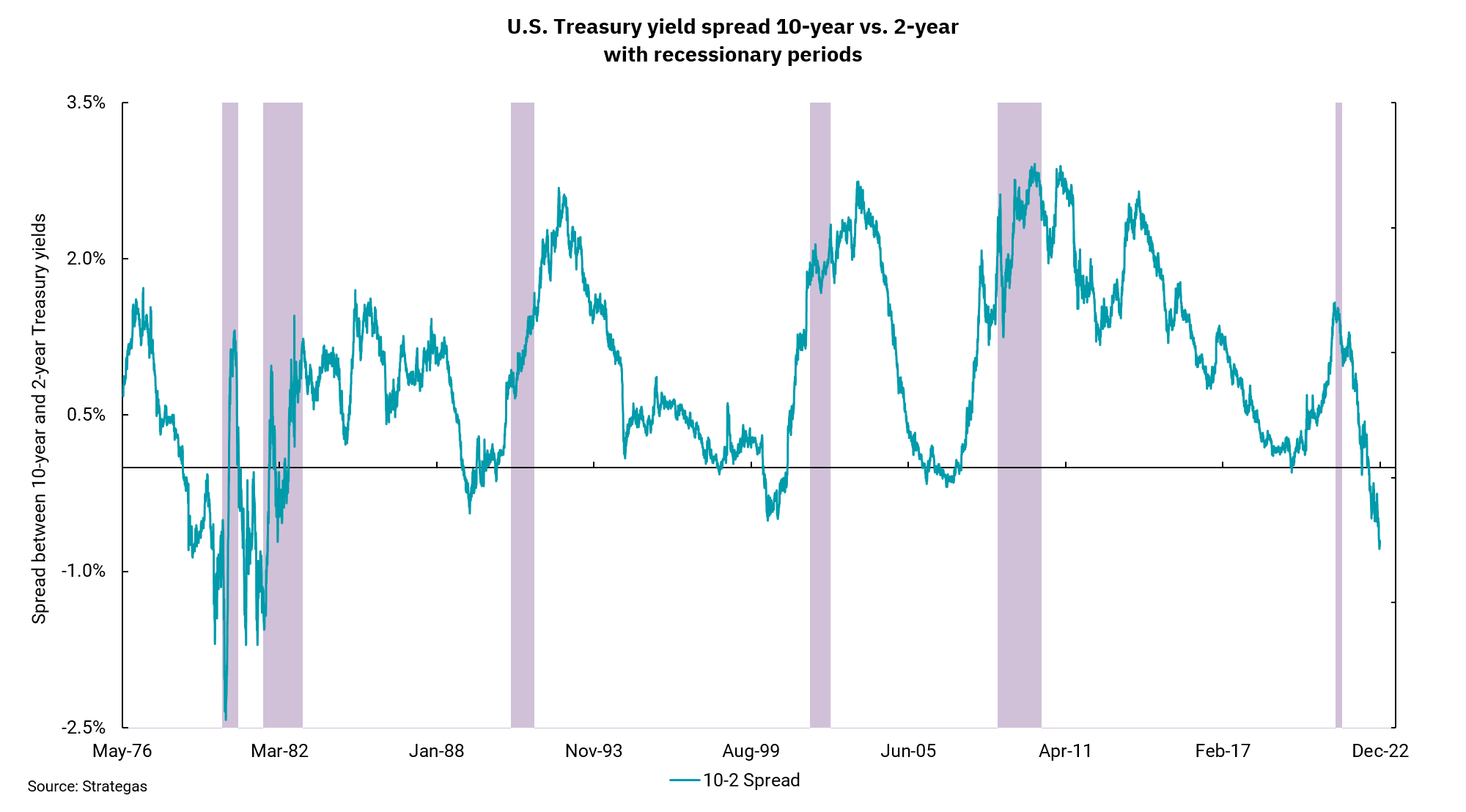

Resetting the fixed-income odometer on Jan. 1, 2023, Wyett anticipates that the Fed may slow its rate increases through the first quarter and consider pausing the moves shortly thereafter. If the maneuvers help steer the U.S. economy to a flat-to-shallow recession, Wyett said, that could allow the key interest rate to hover around 5% deep into 2023.

Perhaps the largest risk to Wyett’s outlook is an over-assertive Fed that maintains its aggressive course deep into 2023—potentially in response to extended stubbornness in inflation.

“Investors are pricing in a 5% Fed Funds rate but if it goes to 6% or 6.5%, we’re going to see more negative rates of return in the bond market,” he said.

Plus, if the Fed overdoes the rate hikes, the country could drop into a deeper recession featuring a sharp deceleration in inflation, a rapid increase in unemployment, significant declines in consumer demand and dramatically reduced corporate earnings.

While central bank policymakers in that scenario could cut rates to stem the negative tide, any corresponding gains in bond valuations would likely be lost amid the broader pain.

“If the Fed started cutting rates mid-year, that would likely mean we’ve had a really bad economic outcome,” Wyett said. “So while that would be an upside surprise for bond investors, it would be problematic for the economy and the stock market.”

Investor perspective

The biggest takeaway for investors? It’s much safer to wade into the bond pool now than it was a year ago.

“If we have any confidence that the Fed can get inflation back down toward its 2% target—and we do, although it’s going to take a while—we believe it’s possible to get returns on bonds that are actually higher than the rate of inflation,” Wyett said. “As an investor in 10-year bonds yielding in the 4% range and believing that will exceed the inflation rate by as much as 2% for eight of those 10 years with minimal credit risk, that’s a pretty good deal.”

More pointedly, Wyett said although short-term issues currently feature better interest rates than their long-term siblings, the risk is higher that yields will have declined when those investments mature in two to three years.

“For longer-term investors, it makes more sense to keep invested for a longer period of time at a higher rate,” he said.

Wyett added that a grim outlook for future tax implications raises the attractiveness of tax-free municipal bonds, although the exclusions may increasingly come under fire as lawmakers wrestle with soaring debt service requirements on $31 trillion worth of national debt. The Congressional Budget Office projects that interest payments alone will more than triple over the next 10 years, jumping from $399 billion in 2022 to $1.2 trillion in 2032.

“The math of debt is the same, whether we’re talking about you and me or the federal government,” he said. “It ultimately becomes a budget issue as you’re spending money which adds money to the debt, which is why you’re having to spend this money in the first place.”

2023 Market Outlook

BOK Financial investment experts Brian Henderson, Steve Wyett and Cavanal Hill Investment Management President Matt Stephani provide their outlook on key issues affecting the economy and financial markets in 2023.