US debt costs may rise in years ahead

Distribution of US Treasury borrowing as significant as size

Although many markets and analysts took the U.S. Treasury's recent announcement that it would borrow less than expected in the last three months of 2023 as positive news, there's a likely downside that could impact the federal budget down the road.

"The surprise came in the distribution of shorter-term bonds for auction versus longer-term bonds," said BOK Financial® Chief Investment Officer Brian Henderson. Since U.S. Treasury bills were already 20% of the government's outstanding debt, markets were expecting most of the Treasury's remaining 2023 bond issuance to be in longer-term securities.

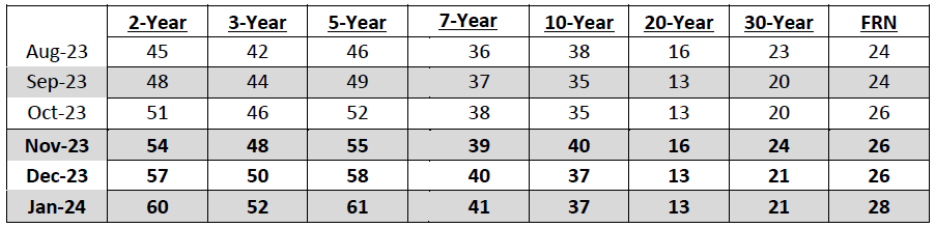

But the Treasury announced the exact opposite, generally aiming to raise more money in short-term Treasury bills rather than in long-term maturities because there's greater demand now for shorter-term securities. For instance, as of Nov. 1, the Treasury plans to auction $54 billion in 2-year notes versus only $24 billion in 30-year notes in December. Then, in January, those expected figures are $60 billion for 2-year notes, compared to $21 billion in 30-year notes.

"By issuing more short-term bills, the U.S. Treasury increased the possibility there will be more demand at auctions, but there are potential negative fiscal issues that could occur in the future if rates stay high or go up further," Henderson said. "With shorter-term bonds, the bills come due quicker, so if rates are still rising or even close to current levels, then the federal government would have to spend more on interest."

Treasury facing supply-and-demand issues

The Treasury's borrowing plan for the quarter comes as the Federal Reserve—traditionally one of the largest buyers of long-term U.S. securities—has been letting Treasuries roll off its balancing sheet and not buying new ones, as part of its quantitative tightening program to fight inflation. Additionally, some of the largest foreign buyers of long-term U.S. Treasuries—namely, China—have also been reducing their purchases.

As the appetite for U.S. securities from these major buyers has been decreasing, the amount of money that the U.S. borrows by auctioning Treasuries keeps increasing, leading to supply-and-demand issues, experts said.

"The bigger picture here is that all of this increased supply from the U.S. Treasury is coming at a time when Treasury bond prices have been on a downward trend over the last year and a half, since the Fed started hiking rates in March 2022," Henderson explained. "This means the Treasury is coming to the market, while investors are sitting at pretty significant losses from the bonds they already bought. It doesn't inspire people to keep buying bonds, if they keep going down in price because rates are going in the other direction."

Higher interest expenses likely to impact federal budget

"Even with this decreased demand, the U.S. is nowhere near the danger of failed bond auctions, but the Treasury auctioning off more short-term bonds than long-term bonds creates concerns for the federal budget," said Steve Wyett, BOK Financial's chief investment strategist.

"The U.S. government has the majority of its debt financed short term while rates have moved up, which means that this is going to have a material budgetary impact very quickly. It already has, and it's going to get worse from here, even if rates don't go up anymore," he explained.

"This is not a partisan issue; this is a math issue."- Steve Wyett, BOK Financial chief investment strategist

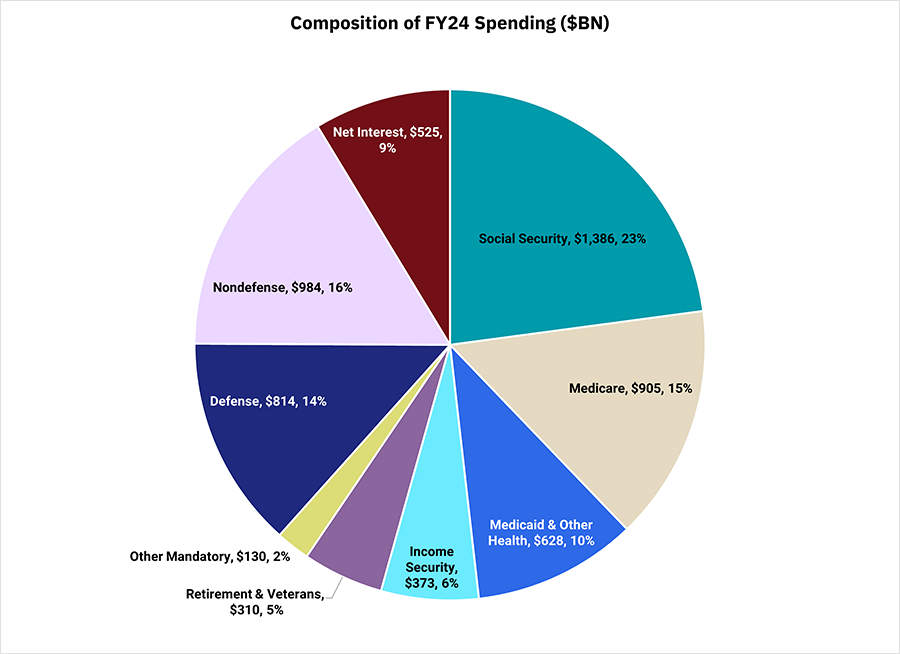

Interest rate expenses are considered part of the federal government's discretionary budget, which is subject to the annual appropriations process. Part of the problem is that the discretionary bucket is already tight as it is. That's because most of the federal budget is taken up by mandatory spending, which is dictated by law and includes programs like Social Security and Medicare.

Another problem is that the government's interest expenses have already been growing, Wyett noted. Interest expenses totaled 10% of federal spending for the 2023 fiscal year, as of Aug. 30, according to USAspending.gov, which is the official source for spending data for the U.S. government. By comparison, five years prior, net interest expenses amounted to 8.5% of federal spending for the 2018 fiscal year.

Since defense spending, which is also discretionary, is challenging to cut given the amount of global uncertainty, the more the U.S. government's interest expenses grow, it puts further pressure on the remaining 16% of the discretionary budget, Wyett said.

Source: Piper Sandler

Source: Piper Sandler

"It's in that 16% of the budget where everything else lives—national parks, the Department of Labor, the Department of Education, TSA and so on," he continued. "The risk is that the numbers are getting too big, so ultimately one of two things—or a combination of the two—are going to have to happen. Either the government will have to generate a lot more revenue, which means that they'll have to do something on the tax front, or they're going to have to cut spending."

"This is not a partisan issue; this is a math issue," Wyett concluded.