Some downward trend in inflation reported, but not on rent and wages

Slowing inflation may mean smaller Fed rate hikes

The Oxford dictionary defines inflation as “a general increase in prices and a fall in the purchasing power of money”. A relatively simple concept by definition, but defining inflation in an economy as complex as the U.S. or globally is subject to many perspectives, iterations and meanings.

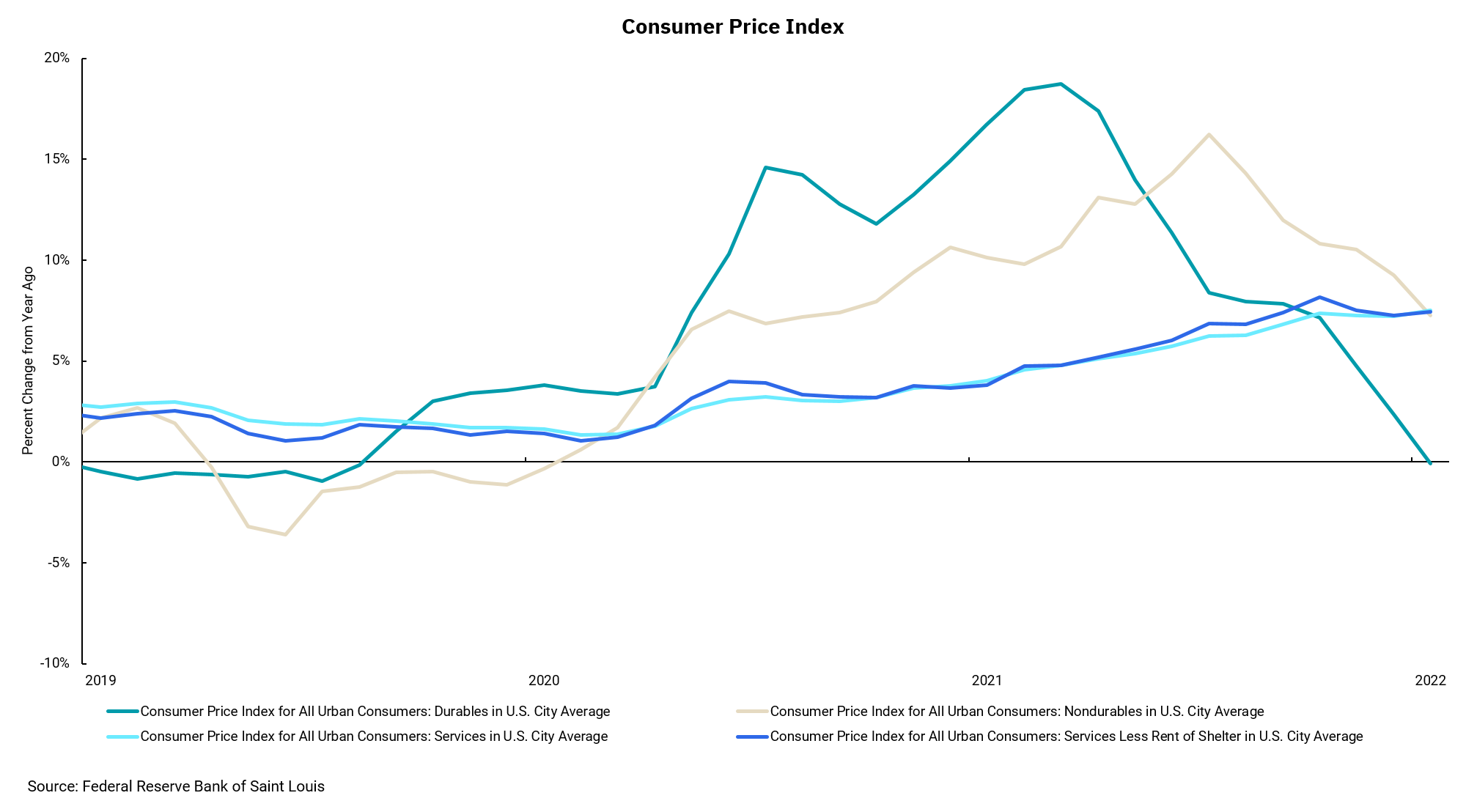

When approaching monetary policy, the Federal Reserve and economists have long known there are areas of inflation that can be highly volatile. These include cyclical prices like food and energy, areas where price changes are longer lasting, and secular areas like rents and wages. Monthly inflation reports such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Producer Price Index (PPI) break down inflation between the headline number including all measures of inflation, and the core number, which is inflation measured on the more secular areas of the economy but excludes food and energy. Between the two, core inflation has been the primary driver of monetary policy decisions.

The overall good news for the Fed, the economy, and U.S. consumers is that inflation is slowing. The most recent CPI report showed headline inflation declined by 0.10%; that’s disinflation, not inflation. Yet the core inflation rate increased 0.30% as rents remain in an upward trend. We have seen price decreases in energy, and while food costs remain elevated, other areas such as apparel, home goods and electronics also show price moderation. The hard part is that wages and rents still present a problem, and these areas will be of primary importance to the Fed.

Our conclusion? The slowdown in overall inflation means the Fed can continue to slow the pace of their interest rate increases. Their most recent move was 0.50% instead of the 0.75% of the previous four meetings and we look for 0.25% in their Feb. meeting. The Fed is still targeting 5-5.25%, and we think they will get there, but the pace of interest rate increases is slowing and inflation will continue to fall.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)