The U.S. dollar maintains its dominance

It’s still best suited as the global reserve currency

As we exit the global pandemic, it is clear that the impact of COVID-19 will be felt for years, if not decades. The business model risk of having all, or a material part, of one’s production overseas, was highlighted as China pursued its zero-COVID policies and disrupted supply chains.

On another front, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine put an end to the idea that a highly interconnected global economy would keep countries from taking unwanted military action. And the U.S. response to the invasion was important as well. Not only did we provide significant weaponry and fiscal support to Ukraine, but we also restricted Russia’s ability to access their dollar-denominated reserves, which were held in our financial system. This action has led a number of countries to re-assess their holdings of dollars. This is not unlike the way companies are now reassessing the risk of having all or a material portion of the production overseas.

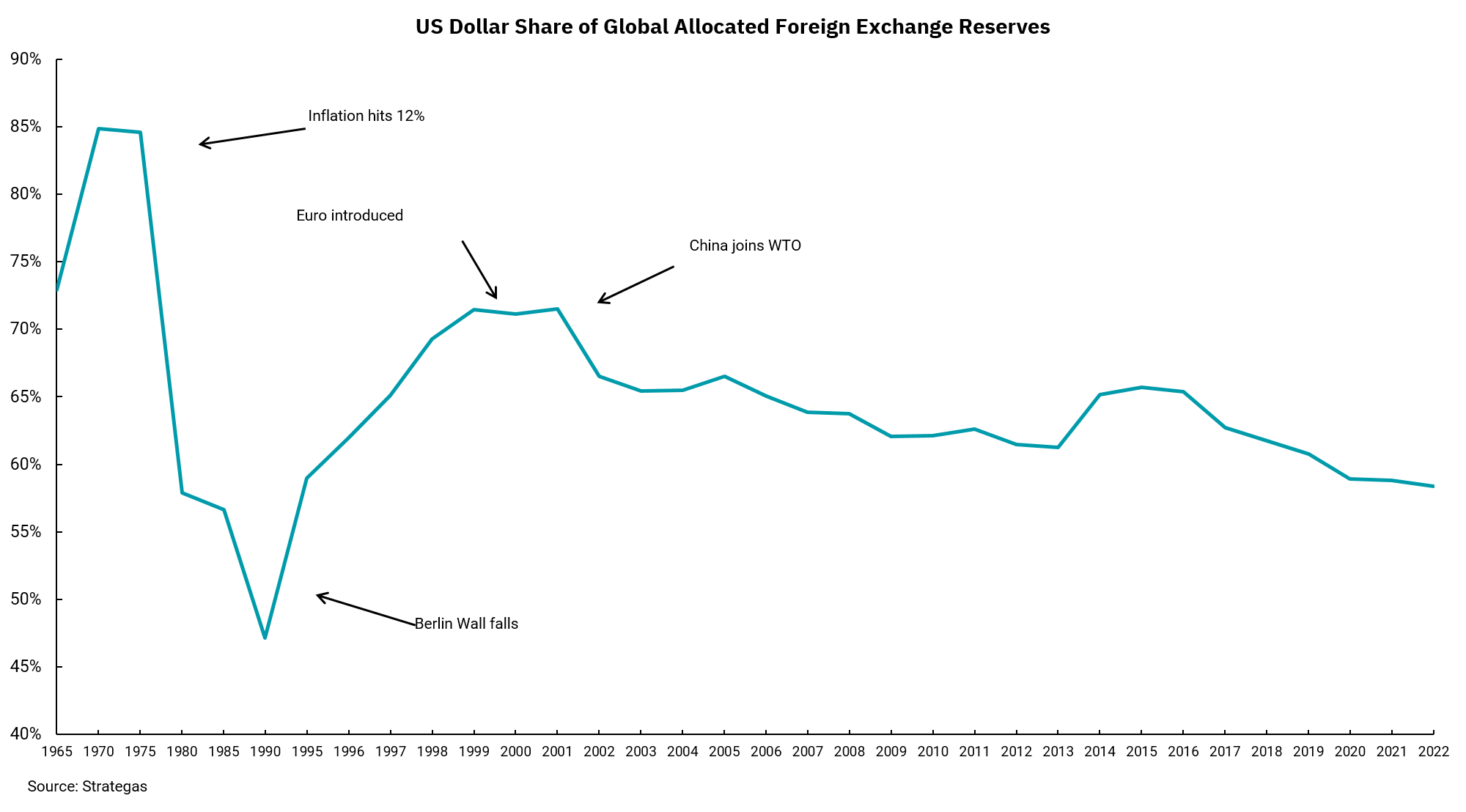

After World War II, the U.S. was almost the only country with economic productivity, and the use of the dollar in commerce soared globally. However. the onset of the Cold War began a period of reduced dollar dominance which ended as the Berlin Wall fell and the age of globalization began. The creation of the eurozone as an economic entity and currency and the joining of the World Trade Organization by China capped the use of the dollar, but it remains, by far, the largest currency within the global economy.

At present, the dollar represents about 58% of global reserve currencies. The next largest currency is the euro, at 15%, followed by the yen. Importantly, for any currency to serve as the world’s reserve currency, it must be free floating in price, with minimal flow restrictions. This means currencies like the Chinese Yuan are far from being able to serve this purpose. Our current fiscal path may not be sustainable over the long term, but we are far from seeing the dollar’s end as the global reserve currency.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)