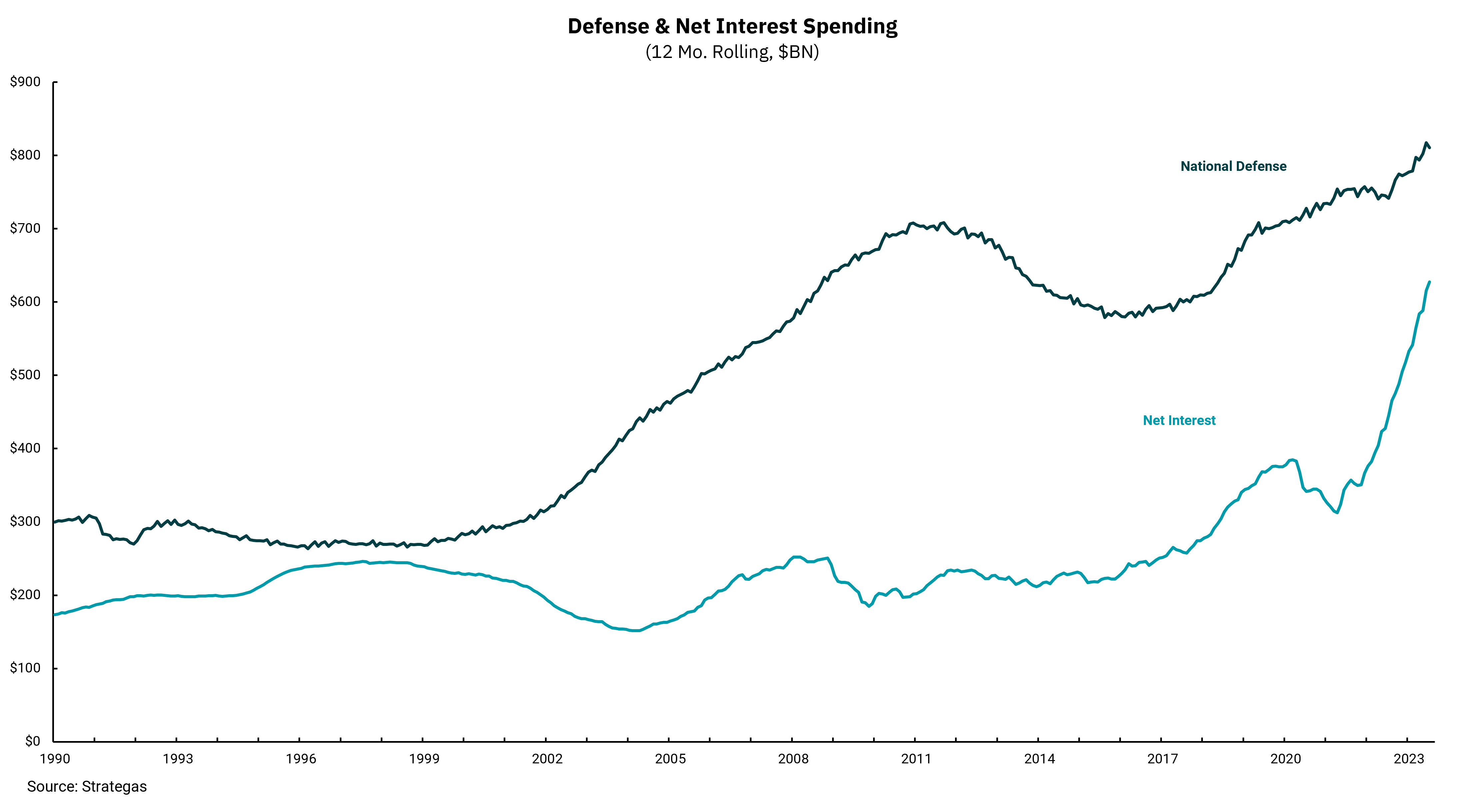

Government interest costs sharply rising

Defense spending is still higher, but gap closing

As we consider the path of spending at the federal level, many factors must be considered. Chief amongst them is that the majority of federal spending is mandatory. Some 60% of the federal budget does not go through the annual appropriations process, where Congress votes to provide monies to various programs. This part of the budget includes social security, Medicare, Medicaid, veterans benefits and other forms of income security. With much of this part of the budget tied to inflation, we have seen annual increases over time, particularly recently, as social security recipients received an 8.7% cost of living adjustment (COLA) for 2023. Inflation is lower now than last year, so inflation-driven increases should slow, but there will still be increases in spending.

Of the roughly 40% of the budget subject to the annual appropriations process, the two biggest line items are defense spending and net interest on federal debt. As our chart shows, there has been variability in these two items over the years, but recently both have been increasing. How defense spending goes from here is a matter of debate, although the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, which suspended the debt ceiling and avoided a default on our debt, guaranteed small defense spending increases between now and January of 2025, when the act ends.

The direction of interest expense over the foreseeable future is more certain: higher. The combination of an increasing amount of outstanding debt and higher interest rates in response to inflation has resulted in a very fast increase in net interest expense. Additionally, over 50% of our outstanding debt will mature over the next three years, resulting in a relatively quick repricing higher of outstanding debt. At present, a significant part of new Treasury debt issuance is in the form of short-term Treasury bills. Financing our spending in this way during the pandemic meant new debt could be added with very low cost as the Federal Reserve kept short-term interest rates pinned near 0%. The now inverted yield curve means this financing is more expensive than longer-term bonds, which is resulting in a very fast increase in interest expense.

The gap between defense spending and interest costs is narrowing rapidly and could soon close. Higher interest expense is also eating a larger portion of tax revenues, where we now spend about 14% of tax revenue to pay interest. All of this is to say, finding a way to reduce spending is hard, and higher inflation makes the job even more difficult.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)