Watching the ‘canary in the coal mine’

Issuances of Ginnie Mae mortgages are up. What does that mean for housing?

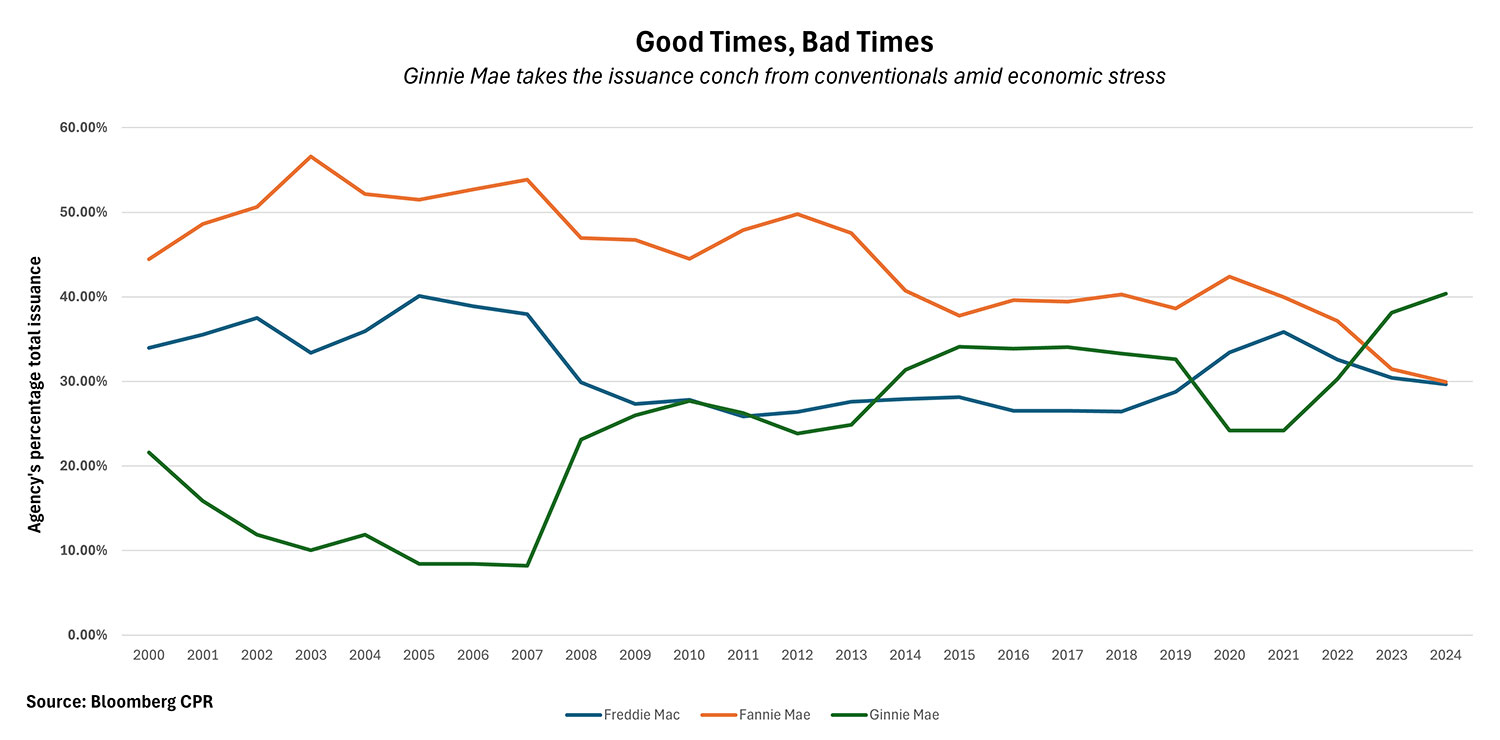

In May, Ginnie Mae mortgages accounted for 40% of all agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issued—the highest figure this millennium, according to data from Bloomberg.

On one hand, the surge in these mortgages makes sense. Ginnie Mae tends to serve first-time homebuyers, as well as low- and moderate-income, rural, tribal and veteran home borrowers who might not qualify for a conventional loan. Between persistent inflation, elevated rates and still-high home prices, it’s no secret that it’s difficult for many people to afford a home these days.

On the other hand, the surge in these mortgages may have serious implications for not just the housing market, but also the U.S. economy as a whole. Simply put: an increase in Ginnie Mae issuance, such as we’re seeing now, is usually a sign that the housing boom is over and that the economic boom is getting long in the tooth.

Ginnie Mae borrowers tend to be more vulnerable to financial stress

So, why are high issuances of these mortgages the proverbial “canary in the coal mine?” For one, it means that more people are struggling to afford a home—and struggling financially in general. While there are more upfront requirements, Ginnie Mae borrowers have to meet far less stringent eligibility requirements than those applying for conventional loans, so when times are tough, Ginnie Mae loans become more common. That’s despite the fact home sellers tend to be less willing to work with these potential buyers than with bidders using conventional loans because of the added time and effort necessary to close non-conventional loans.

Take debt-to-income ratio (DTI), for example, which is a borrower’s total monthly debts divided by their grossly monthly income and converted to a percentage. For Ginnie Mae borrowers, that figure is usually is in the mid-40s, whereas it’s usually in the mid-30s for conventional borrowers, according to Bloomberg CPR. The problem: the more debt you have relative to your income, the harder it is to pay that debt, including your mortgage.

Then, there’s credit scores to consider. Ginnie Mae borrowers also tend to have low FICO scores. For example, the average FHA borrower has a score of 670, whereas your average conventional borrower is in the 760 range, based on Bloomberg CPR data.

Perhaps the most telling figure is the loan-to-value ratio (LTV) of these loans, however. LTV is the amount borrowed as a percentage of the value of the home. For conventional loans, the LTV is usually in the high 70s or low 80s; for Ginnie Mae loans, it most often is seen in the high 90s, according to Bloomberg CPR. The latter means that nearly the entire value of the house has been borrowed, so there is a higher potential for the house to go underwater in the event local home prices drop, trapping people in homes they cannot afford to sell.

In understanding the implications of an increase in Ginnie Mae loans, it is important not to forget the differing characteristics each presents and what that could mean for borrower performance. For instance, during 2020 the percentage of seriously delinquent (90 days or more behind on mortgage payments) for conventional 30-year borrowers hit 2.7%, at the same time it was 7.1% for Ginnie Mae 30-year borrowers.

What this trend means for the financial system

It’s also important to keep in mind that with Ginnie Mae loans come higher risks that extend beyond any single mortgage. Due to these same financial characteristics—higher DTI, lower credit scores and high LTV—Ginnie Mae borrowers tend to have less financial cushion than conventional borrowers. As a result, an unforeseen event such as loss of a job can become a major financial emergency that may make paying the mortgage difficult. So far, unemployment has remained low, despite the high-rate environment, but that could change—and when unemployment starts to increase, it typically does so rapidly.

Hence, when Ginnie Mae mortgages account for a large percentage of MBS issued, it leaves the overall mortgage bond sector more vulnerable to a surge in delinquencies and buyouts. Mortgage lenders can help mitigate this risk by keeping an eye on potential borrowers’ credit scores, but even that isn’t a complete safeguard. Credit scores can’t predict everything.

What Fed rate cuts would mean for the housing industry

Although everyone has been closely paying attention to the Federal Reserve and anticipating when they will lower the Federal Funds rate, it may not impact the housing industry as much as one might expect. For example, if the Fed cuts rates while the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is still well above the Fed’s 2% target, the investing world may take the cut as a sign that the Fed is no longer committed to lowering inflation to that level. As a result, mortgage rates may not go down—and may even go up—because investors would then have to reprice their expectations of where inflation is headed and how aggressive the Fed will be fighting it.

The bigger picture may be that consumers are becoming more comfortable with mortgage rates at 7%. After all, prior to the easy money era embodied by quantitative easing (QE), the average 30-year lending rate (using the Freddie Mac conventional 30-year) was just over 9%. At the moment, mortgage rates are still low from a historic perspective. Then, as more homeowners get used to the current rate, the house they’ve been locked into because of their existing low mortgage rate might start feeling just a little too small or a little too outdated. Eventually, we will see more homes go on the market, which would be a welcome relief for many buyers. As the saying goes, time heals all wounds.

Christopher Maloney is a mortgage strategist with BOK Financial Capital Markets. In the role, he conducts daily data analysis, watches mortgage-related news, studies economics and speaks frequently with other market professionals to keep a close eye on the mortgage bond market.