We live in a headline inflation world

Consumers feel the impact of inflation building on itself

For many consumers, there’s a tale of two inflations.

There’s the story of inflation they learn through the news—that year-over-year inflation has moved downward from its peak but is still higher than the Fed wants it to be.

Then there’s the story of inflation that they experience in their everyday lives—more expensive household bills plus higher prices at the grocery store, at restaurants and sometimes at the gas pump.

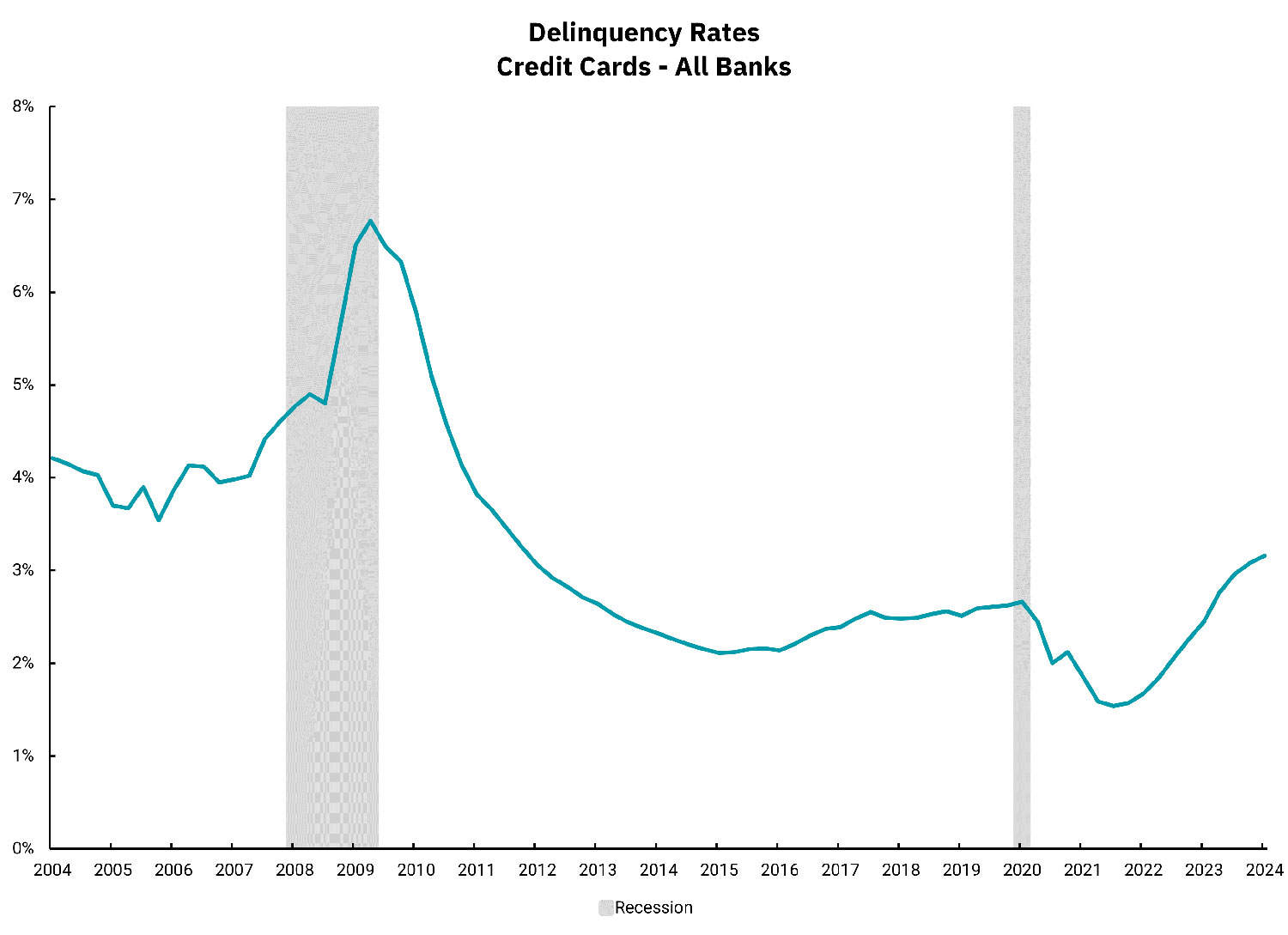

Lower-earning consumers are experiencing the negative effects of these higher prices, coupled with high interest rates, the most. As BOK Financial® Chief Investment Officer Brian Henderson explained, “Inflation certainly hurts low-income consumers more because they don’t have a financial cushion. Without significant savings or wealth, they don’t have a lot of flexibility when car insurance companies are raising rates or landlords are increasing rent. Credit card delinquency rates are high but not on an alarming level. These consumers feel the brunt of the affordability issue.”

And so, struggling consumers may wonder: if inflation is getting better, why am I stretched so thin?

It’s not that one story of inflation is factual and the other is not. It’s that economists and everyday consumers tend to be thinking of two different things when they’re talking about inflation getting better or worse, said BOK Financial Chief Investment Strategist Steve Wyett.

Inflation ‘getting better’ might not feel that way to consumers

“When economists, the Fed and politicians say that inflation is getting better, we mean that the year-over-year rate of inflation is lower than it was the previous month,” he explained. In other words, while prices are still rising, they are not rising by as much as they were before. But the bottom line is that prices are still rising.

Meanwhile, for many consumers, the idea of inflation “getting better” means that prices are dropping. When that happens, that’s technically deflation. For instance, used car and truck price were down 9.3% year-over-year, according to the May Consumer Price Index (CPI), which represents deflation, even as prices in the overall economy are still in inflation.

While overall prices dropping might, at first, sound positive, deflation is considered negative by economists because of its association with a spiral of decreasing economic activity. On the other hand, some degree of inflation is normal in a growing economy, represented by the Federal Reserve’s target for year-over-year inflation of 2%.

Consumers experience the aggregate effects of these yearly increases in inflation, whereas economists tend to focus on the rate of change, and therein lies the disconnect, Wyett said. “From a consumer standpoint, inflation builds on itself. If you go back to before the pandemic, aggregate headline inflation is up 20% since then. That means consumers have lost one-fifth of their spending power.”

“So, when we say that inflation is ‘getting better,’ that’s correct from an economic standpoint, but it’s still painful from a consumer standpoint because the aggregate price level is still higher.”- Steve Wyett, BOK Financial chief investment strategist

Take, food inflation, for example. Food prices were up 2.1% year over year, according to May CPI, which means that consumers were paying 2.1% more for food than they were a year ago. That doesn't sound like a large increase. However, taking a slightly longer view, U.S. food prices rose by 25% from 2019 to 2023, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Only transportation rose more during that time. And so, while year-over-year price increases may seem small, the aggregate effects of those increases are sometimes much larger, which we’re all feeling in our wallets.

The Fed focuses on core inflation … but consumers may not

Even when considering the monthly inflation reports, there is sometimes a disconnect between what’s prudent for the Fed to focus on and what may impact consumer wallets most.

For the Fed, “core” inflation is the most important inflation data released each month because it excludes food and energy prices due to their volatility. “If the Fed tried to implement monetary policy looking at those very volatile areas, they would be jumping up and down on interest rates very quickly,” Wyett explained. “That’s not additive to what the Fed is trying to accomplish with monetary policy.”

However, for consumers, food and energy prices are often large concerns, especially for lower-income households because these core necessities take up a larger portion of their incomes even when they tend to be buying less. In 2022, the latest year for which there is data available, the lowest-income households spent an average of $5,090 annually on food, making up over 31% of their annual incomes. By contrast, the highest-income households only spent 8% of their incomes on food, according to the USDA.

Although wages on the lower end of the income spectrum have increased more than wages on the higher end, the wage increases have not kept up with the increase in cost of living, Wyett noted.

“And this is where there is no difference of opinion between how the Fed and economists think and how consumers think about inflation: It hurts those who can least afford it the worst,” Wyett said. “It highlights why the Fed says we must get inflation down and the importance of what they’re doing to lower it.”

Now decides the future

View the interactive video, a downloadable report and other articles prepared by the BOK Financial investment management team.