The energy transition needs to be ‘done right’

High consumer prices, less U.S. competitiveness and still-high global emissions must be avoided

Although Donald Trump's election as U.S. president likely slowed the move towards lower-emission energy sources, experts say the transition is still happening—and that the stakes are high for managing it correctly.

"The worst approach is a really haphazard policy for the energy transition that results in nothing more than lower emissions in the United States but much more expensive power," said Matt Stephani, president of Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc., a subsidiary of BOKF, NA.

There's also the chance that, if the U.S. stops burning coal and it becomes more expensive to manufacture goods domestically because of higher energy costs, manufacturing will move to other countries such as India that continue to burn coal for cheap energy, Stephani added. In that scenario, global emissions would continue to rise, even though the U.S. would have stopped burning coal—and may have lost some manufacturing in the process, he noted.

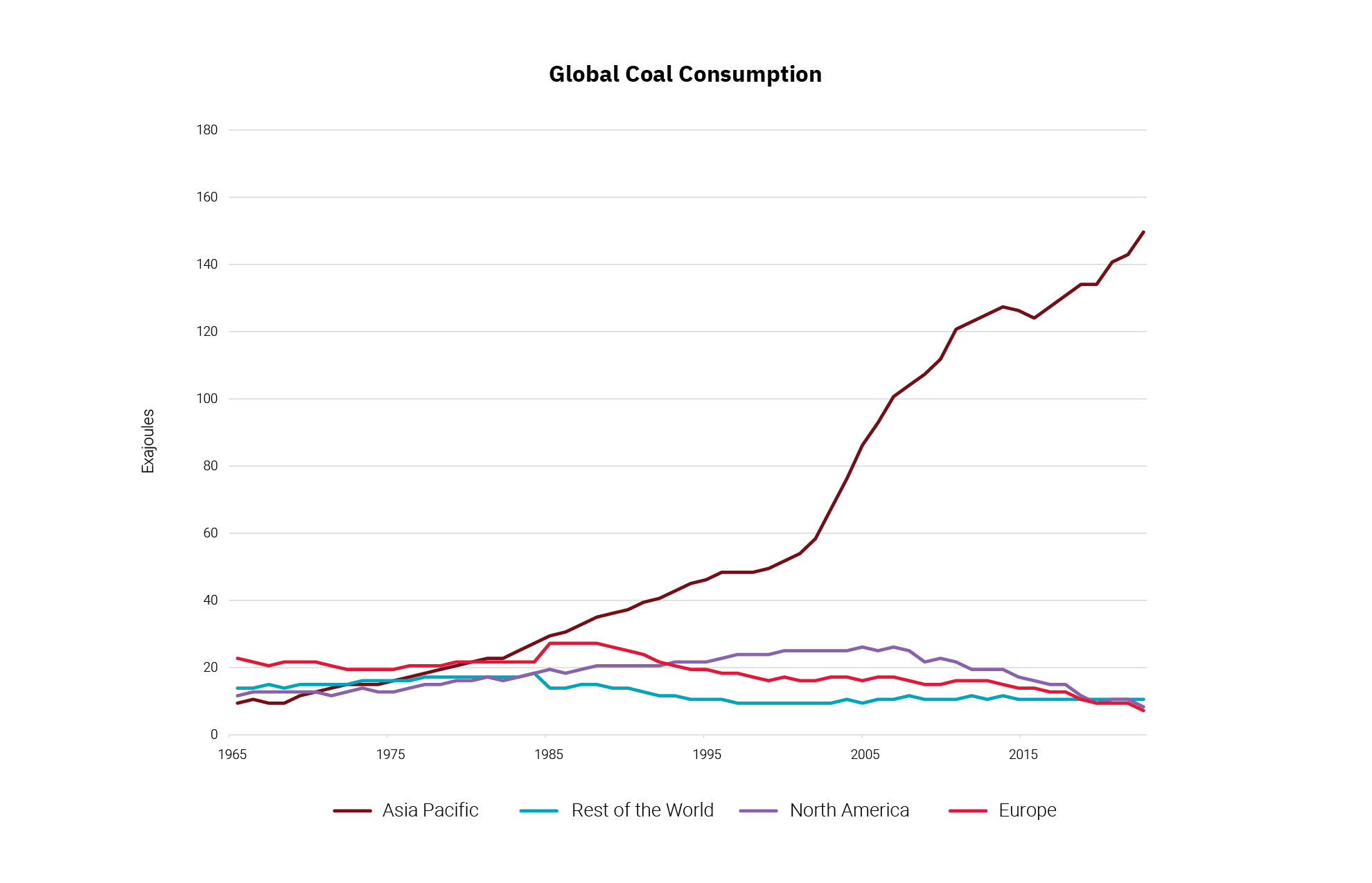

Already, the Asia-Pacific region consumed more coal in 2023 than other regions of the world combined, according to data from the Energy Institute's 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy.

And it's not just the current U.S. manufacturing industry that's at stake. Access to cheap energy is going to be particularly important in determining which countries will be economic powerhouses over the next 30 years and "who will win the manufacturing and technology race currently being driven by artificial intelligence (AI)," Stephani said.

Energy transition might be slower than expected

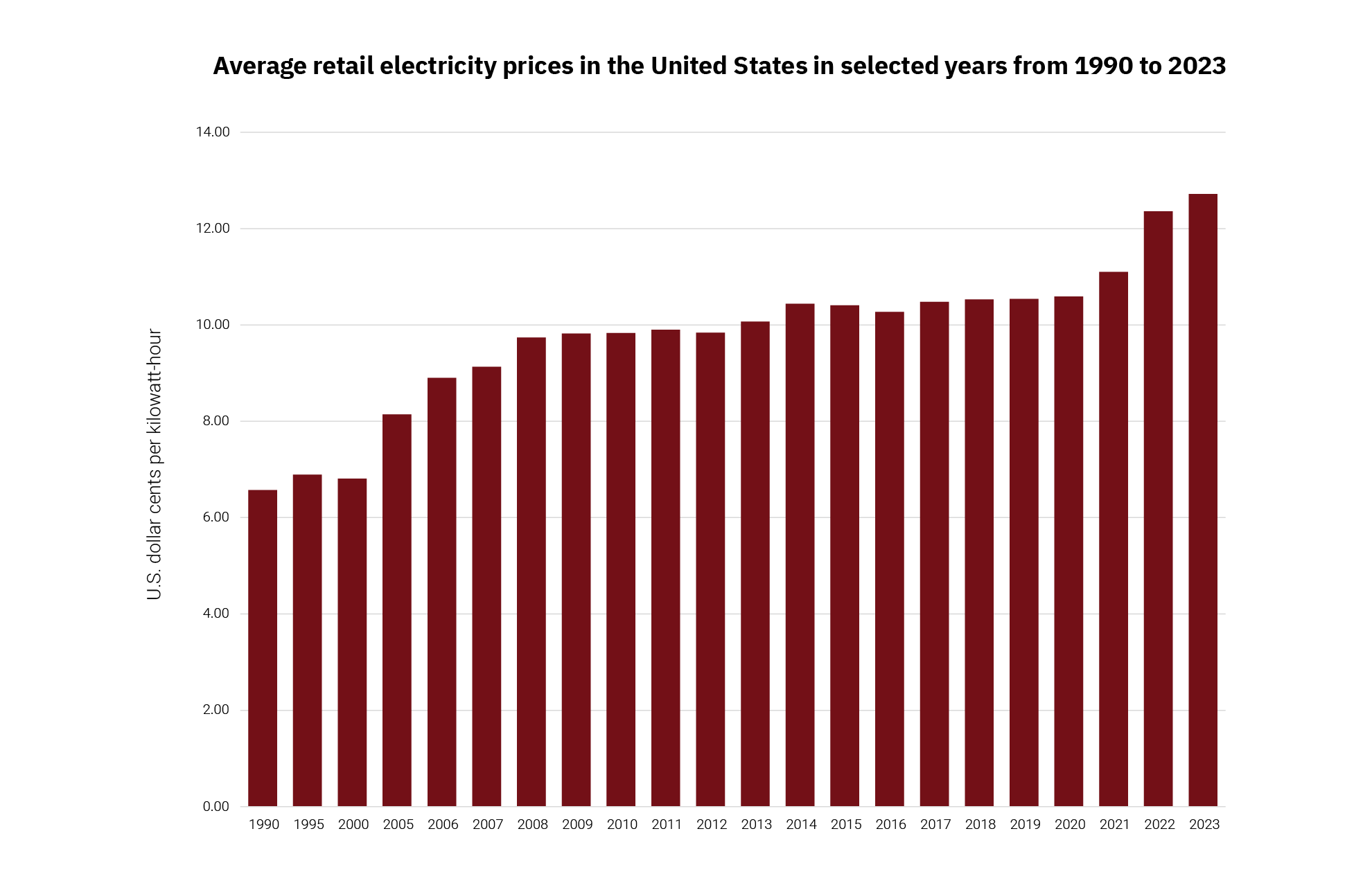

Right now, the U.S. has some competitive advantage in terms of cheap energy. In 2023, the retail price for electricity in the U.S. was an average of 12.72 cents per kilowatt-hour—the highest figure in the recorded period of over three decades, but one of the lowest electricity prices worldwide, according to figures from Statista.

Source: EIA

© Statista 2024

However, that competitive edge could decline if the U.S. looks at emissions alone in determining which energy sources to use, rather than also considering the cost of the energy and its reliability. As Stephani explained, "We must have a policy that results in cleaner emissions and lower cost energy. To make an energy transition successful, we have to meet both objectives."

So far, meeting both objectives has been a struggle, experts agreed. "We're seeing the reality that some of the green initiatives are not working as well as people thought they were going to," said Dennis Kissler, SVP of trading for BOK Financial®. He pointed to British Petroleum's (BP) decision to scale back its focus on offshore wind projects, amid higher costs from technical and supply chain problems plus higher interest rates.

However, green initiatives will still continue to grow over time, Kissler added. "We're going to have more wind farms in two years than we have now. We're going to have more solar than we have now. However, with the Trump administration, I think that it's going to be more of a fair value of 'how much more efficient is natural gas to these things?' And so, the transition is going to be slower than what's anticipated, but it's going to move forward."

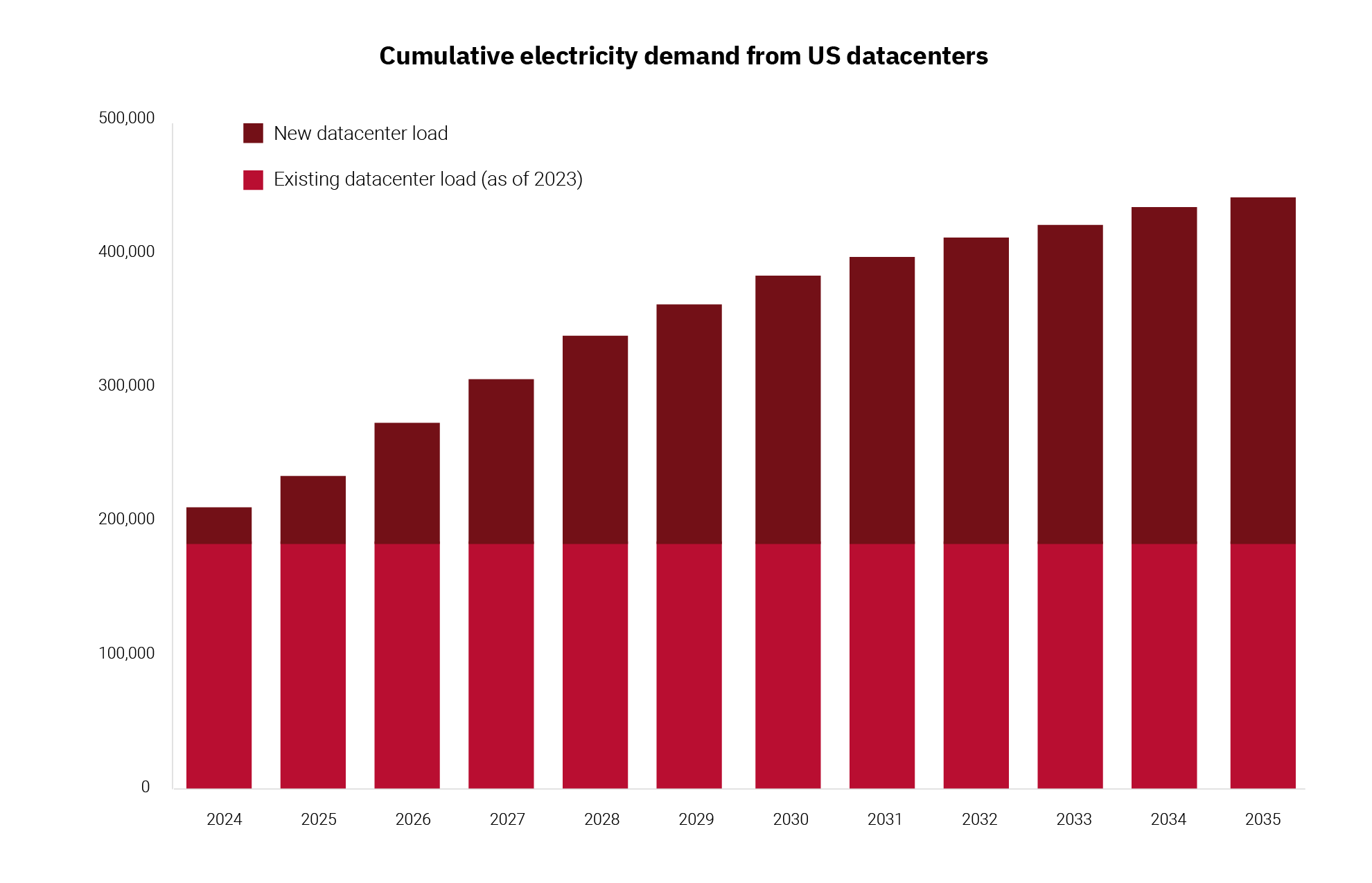

Increasing the complexity of the issue is the fact that this transition is occurring at the same time that U.S. energy demand is expected to increase substantially in the years ahead, driven by the power needs of large data centers and AI. Data center demand could add as much as 80 gigawatts (GW) to U.S. load demand by 2030, according to a McKinsey analysis. Data centers currently use around 3.5% of the power on the U.S. grid—and, if that goes to 8% or 9%, "the impact would be exponential," Kissler said.

Sources: S&P Global Commodity Insights; S&P Global Marketing Intelligence 451 Research

©2024 S&P Global

Then, there's the unforeseen power needs of advanced AI systems to consider. For instance, Microsoft's planned Stargate AI Supercomputer may require as much as four to six GW of power, almost the equivalent to the power needs of a large city such as New York.

What will power this new technology?

In the short-term, experts believe that natural gas will be used to power AI and data centers, as the use of coal burning declines. "We're going to need bigger power plants to produce that volume of electricity, and I expect that's going to draw on natural gas," Kissler said. "That's the cleanest alternative and the most efficient source."

"Wind power's not enough to do it. Solar power is not going to be enough to do it. Those are going to help in a way, but a lot of those resources are inefficient, especially wind power," he continued.

As a result, the U.S. power sector's demand for gas may increase by 10% to 30% by 2030, compared to today, according to analysis by Bloomberg Intelligence. However, natural gas alone might not be enough to meet these immense power demands and, moreover, it might be supplanted by other sources such as nuclear power as the transition toward lower-emissions energy continues, experts agreed.

"I think what's going to happen is many may realize that nuclear is the best of all the possible solutions for the problem, especially when you consider the 24/7 power needs of these data centers, which are going to be the energy hogs in the next 20 years," Stephani said.

Already, support for more nuclear power plants in the U.S. has been growing. Meanwhile, Amazon, Microsoft and Google have been investing billions of dollars in nuclear to power future AI plans and other business.

Nevertheless, a large movement toward nuclear power is still a long way off—at least until the 2030s, Kissler said.

"I think as the younger generation gets older and the technology gets better, they'll forget about things like Chernobyl and Three Mile Island that I saw. Then, nuclear could be a sub power that could take away from natural gas," he continued. "But for the next four to five years, AI is going to pull a lot more demand off the grid and a lot more infrastructure will have to be replaced with power plants that can produce the necessary power. A lot of that's going to from natural gas."

2025 Outlook

A new year is often associated with transformation. Even so, the degree of change ahead in 2025 looks unusually large for the U.S., with potential shifts in trade policy, immigration, regulation and more. BOK Financial's investment management team has prepared its 2025 market outlook as a downloadable report, supplemental articles and a recorded webinar.