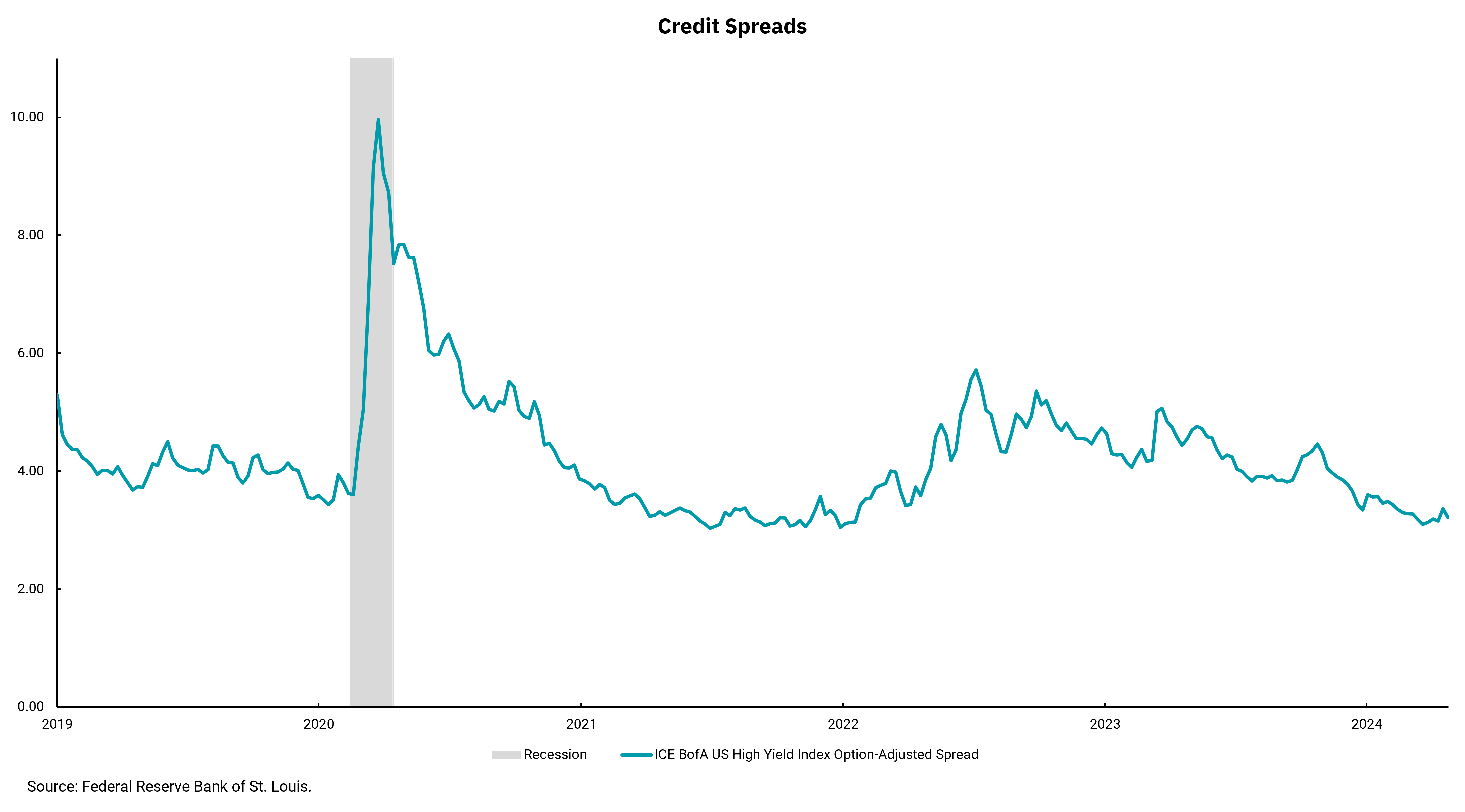

High-yield credit spreads not sounding alarm bells

Lower spreads indicate bond investors see continued economic growth

The “math” of bond returns is, in some ways, easier than the “math” of equity returns. The valuation process of any asset involves making some assumptions about the future. When thinking about equities, the variability of future cash flows, earnings, interest rates and/or dividends can be highly subjective and prone to big swings. Yet when considering fixed income investments, or bonds, the math is much more certain. That’s because bonds are issued at par and also mature at par, resulting in a growth rate of 0%. Cash flows also are more defined, as coupon payments are paid at known intervals between bond issuance and bond maturity. As a result, we normally have lower return expectations for bonds than for equities, based on this additional certainty that bonds provide.

However, when we introduce the concept of credit risk, bond returns can be more variable. Within the bond market, U.S. Treasury securities are assumed to have zero credit risk (an assumption which can be called into question as we approach debt ceiling limits). Meanwhile, everything other than Treasuries carries some additional measure of risk. Since we know the growth rate of bonds is zero, the only way for bond investors to demand a higher rate of return, or accept a lower rate of return, is to adjust the price they are willing to pay for a bond. When they’re only willing to pay lower prices, it results in higher yields. When they’re willing to pay higher prices, it results in lower yields. The lower the prices that investors are willing to pay, the larger the spread between a Treasury security and a bond with credit risk. The inverse is true for higher prices.

Our chart this week plots the spread between high-yield bonds (which have a lower credit rating) and a Treasury security. When investors demand greater return, the spread goes up. When they demand lower return, the spread goes down. Widening spreads indicate that bond investors see an environment where the lack of economic growth might make the payment of bond coupons more difficult, resulting in somewhat higher levels of defaults. Within this environment, investors will demand a higher rate of return to accept this higher level of risk. Meanwhile, lower spreads are an indication that bond investors see a period of continued economic growth. In this environment, companies will be able to pay their bond coupons, so there will be lower levels of defaults. As a result, bond investors are willing to accept somewhat lower yields.

Hence, as we think about the broad economy, credit spreads can be a very useful tool to keep in mind. Many will remember the consistent calls for a recession in 2023—and the reasons to expect this were valid. However, as we can see in the chart, the spreads demanded by investors in high-yield bonds never signaled that a recession was in the cards. Instead, spreads narrowed as the year went on and we saw economic growth accelerate. It can be difficult at times to separate “noise” from “signal,” but credit spreads are at the top of our “signal” list.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)