Fewer rate cuts ahead?

Shifting expectations impact borrowing costs, investments and economic growth.

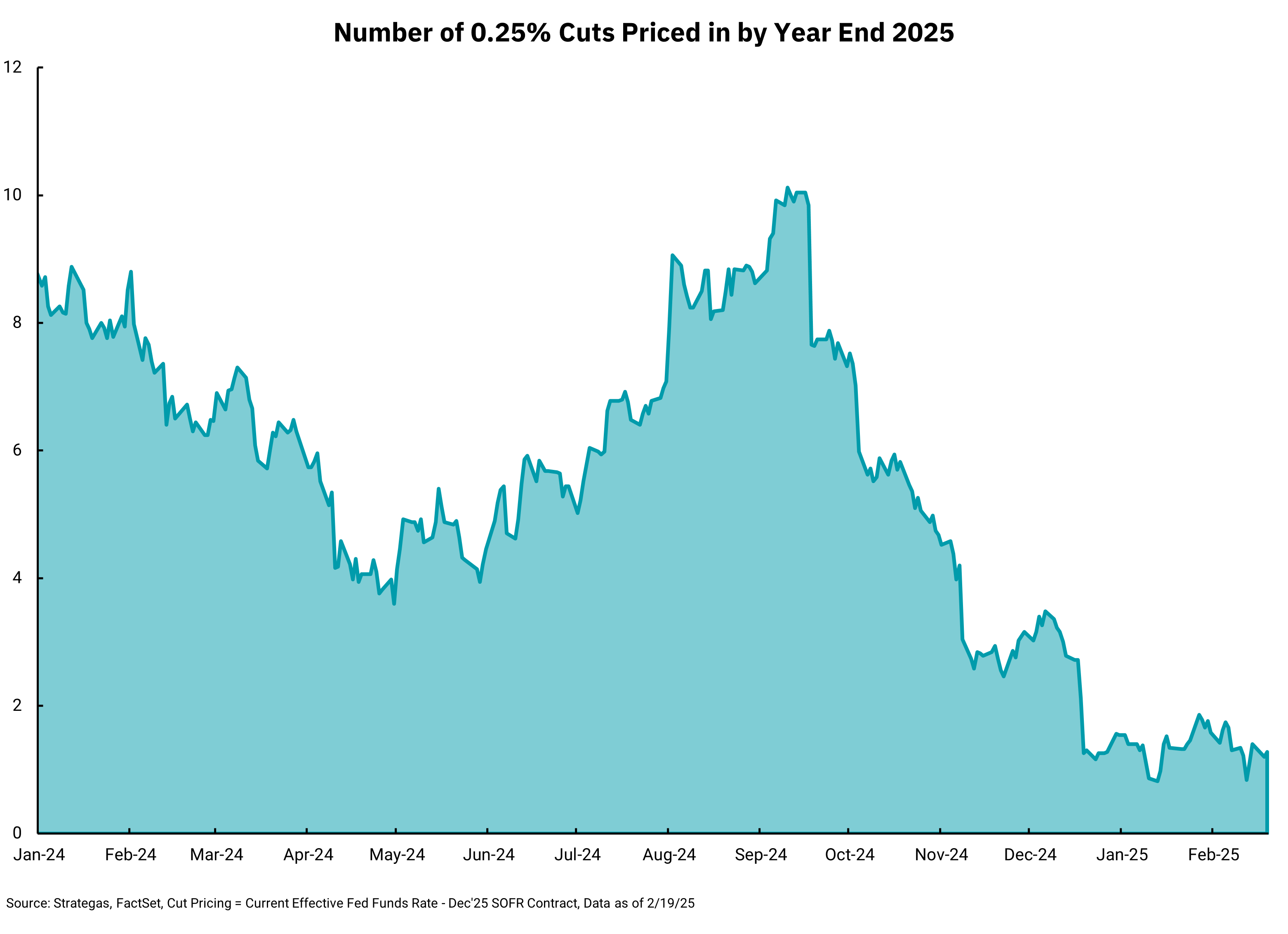

Our chart this week shows a clear decline in the number of rate cuts expected out of the Federal Reserve by the end of this year. A "rate cut" is defined as a move lower by 0.25%, or 25 basis points. This means we must acknowledge that part of the drop is because the Fed has already reduced rates by 1%, or four cuts in "rate cut" parlance. In fact, their first move to start lowering rates back in September 2024 amounted to two rate cuts, as they lowered rates by 0.5%, or 50 basis points, at that meeting. They followed that action with additional rate cuts of 25 basis points at their November and December meetings.

We arrive at the total number of expected rate cuts by considering how many times the Fed has lowered rates and the ultimate rate at which we think they will stop lowering rates. This means that if we had the same expectations of where rates would end up today as we did back in September 2024, we would still be expecting six more rate cuts (10-4=6). The fact that we are now expecting only between one and two more rate cuts means there has been a significant shift upward in where we expect the Fed to stop raising rates. We call this stopping point the terminal rate, or you might have heard the term "r star" (r*). This terminal rate, r*, is defined as the interest rate where the Fed is neither restrictive nor stimulative in monetary policy. It is also called the "neutral rate."

One might reasonably ask what that neutral rate actually is. Is it 2%, 3%, 4%? The movement in this chart indicates the market is shifting its definition of this neutral rate. Economic growth has remained extremely resilient, with unemployment at 4% and more open jobs than unemployed people, despite the Fed aggressively raising rates to 5.25-5.5% before beginning their current rate-cutting cycle. And so, while the Fed may feel that rates are restrictive above 5%, economic data might indicate they are not as restrictive as they thought; hence, they don't need to cut rates nearly as much to be "neutral."

This concept might feel esoteric and hard to understand, but it is vitally important as we consider the path of interest rates, growth and inflation moving forward. If the Fed is not going to lower rates as much as we thought, then borrowing costs will remain higher for companies and mortgage rates will remain high for individual borrowers. At the same time, investors can enjoy higher rates on investments for longer than we thought. Meanwhile, inflation might take longer to reach the Fed's 2% target.

Interest rates also play an important part in the valuation process for stocks. In general, higher rates are a headwind to higher stock prices. To a degree, rates staying higher because business is good is positive, but this could be offset by a lower current value of future earnings. It seems much of monetary policy remains an "art," as opposed to a "science."

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)