Should we be ‘on alert’ for a warning from the bond market?

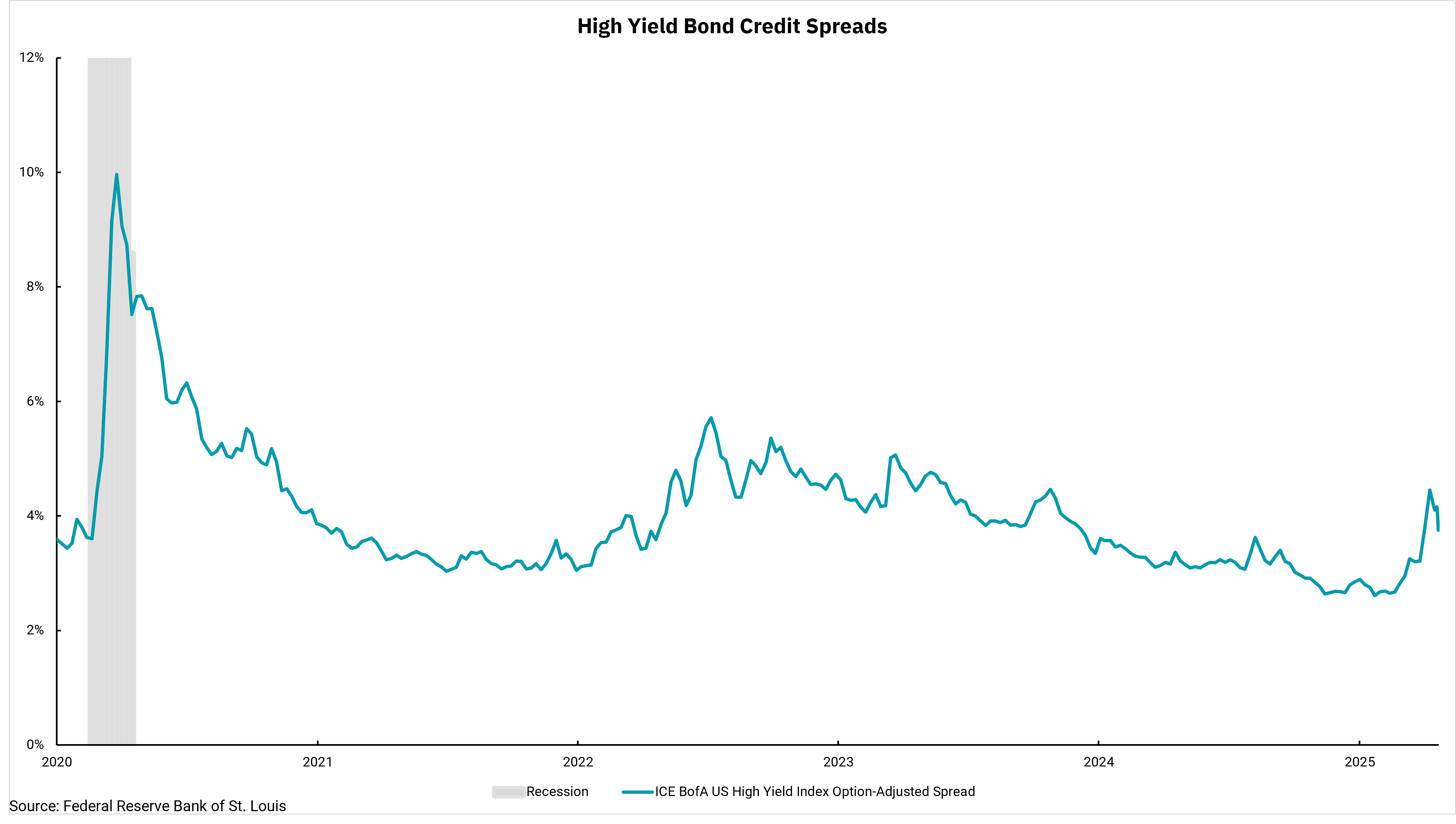

High-yield credit spreads increasing, but still below what’s seen in recessions

You may wonder why economists watch the bond market so closely, despite the stock market getting most of the press. For one, the bond market is a multiple of size compared to equities. Plus, since the "growth rate" on bonds is zero, the "math" of the bond market is easier, as future cash flow and the terminal value are known figures. (That's because bonds are primarily issued at par and—absent a credit event, which is the point of this week's chart—mature at par. The only "return" for an investor is embedded in the regular cash flows, or coupons, over the life of the bond.) And yet, there's a lot of information to be gleaned from this "simple" market.

Of course, we watch the absolute level of Treasury rates, keeping in mind that interest rate policy is the Federal Reserve’s primary monetary policy tool. Additionally, experts watch the movements and levels of shorter-term bonds, which are more heavily influenced by Fed policy, and longer-term rates, which are more influenced by the perceived level of future economic activity and/or inflation. This is where the shape of the “yield curve” comes into play. You might recall an elevated level of angst amongst economists as the yield curve inverted for an extended period a couple of years ago. Past periods when short-term rates exceeded those on longer-term bonds were followed by economic weakness and/or recessions. However, to date, the most recent period of yield curve inversion has not resulted in a recession, and we are now back to a positive sloping, or normal, yield curve with short-term rates below long-term.

While Treasury securities are considered “risk-free” from a credit standpoint, this is not true for other issuers like corporations. Economic activity changes can make corporations more or less likely to pay their bonds as promised. In general, if the economy is good and corporate cash flows and profits are positive, we would assume the repayment ability of corporations is improving. In this environment, investors would demand less spread between risk-free treasuries and riskier corporate bonds. Conversely, a slower economy might increase the risk of default and lead investors to demand a higher spread to treasuries to compensate for this risk. Again, unlike stocks, bond investments do not have a “growth” aspect.

Knowing all this, allows us to look at charts like the one we have this week, which shows, in real-time, the spread being demanded by investors in bonds--in this case, high-yield bonds, where sensitivity to economic growth is very high, as a guide to the economic outlook. We can see clearly the recent increase in spreads. Does this mean a recession is imminent? At this point, we would say no, as spreads are still lower than in past recessionary periods. However, the direction of the move means we are on alert for the possibility of a warning from the bond market. The stock market might be sexier, but the bond market is the “big dog” in the capital markets.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)