The ‘mixed message’ around U.S. manufacturing

Tariffs, tax incentives and rising productivity are reshaping America’s industrial landscape

KEY POINTS

- Tariffs are raising near‑term costs while tax incentives will take time to translate into increased U.S. manufacturing capacity and jobs.

- Productivity gains, especially as AI expands, mean output has held steady despite decades of job losses.

- Reshoring manufacturing could strengthen economic resilience but also may keep inflation and interest rates higher.

Much has been made of the impact of globalization on the number of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. To be sure, the move to seek lower-cost labor overseas, a trend turbocharged by China's entry into the World Trade Organization in 2002, played a major part in the shuttering of manufacturing facilities across several industries. A key part of the current administration's shifts in trade policy is an effort to bring manufacturing, and its jobs, back to the U.S.

We currently have a “carrot and stick” approach to the issue. The stick is the tariffs being levied on imports, while the carrot is changes to tax policy that incentivize companies to make capital investments in U.S. based manufacturing. The hard part is that there is a timing differential between the impact of the stick and the benefit of the carrot. While the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for October and November provided signs that the price increases from tariffs have been less than feared, the reality is that inflation might fall even faster without them. Ongoing affordability issues from aggregate inflation since the start of the pandemic remain. At the same time, even with announcements of billions of dollars in investment, it will take months, and even years, before new plants and equipment are constructed and ready to hire new workers.

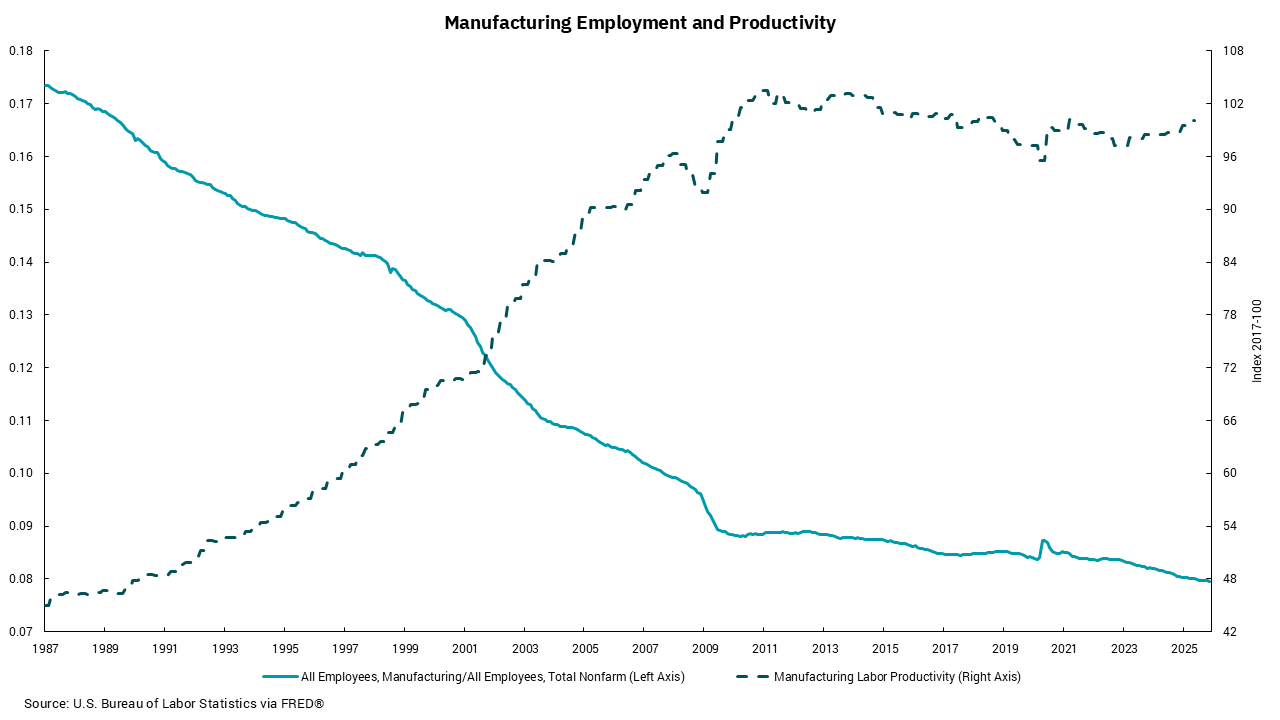

Beyond the impact on jobs within the U.S. manufacturing sector, another massive trend has been underway: increased productivity—and it may accelerate further as artificial intelligence (AI) becomes a bigger part of the U.S. economy. Despite some flattening of gains over recent years, our chart this week shows the material gains in productivity since the mid-eighties. Although there were significant job losses over that period, manufacturing output has remained relatively steady. This does not mean the shift in jobs globally has not had some negative aspects on the U.S. economy and its workers. Indeed, the gains in productivity could mean that manufacturing output would be significantly higher and gross domestic productivity (GDP) growth would be potentially better had this offshoring not happened. At the same time, globalization has been a factor in the decline in inflationary pressures and the long period of low and steady inflation since the mid-nineties.

This mixed message could continue as we make policy changes to bring more manufacturing back to the U.S. Job growth might be better, a positive, but overall costs for producers might be a bit higher, meaning inflation rates could settle at somewhat higher levels. This could lead to the Federal Reserve keeping rates a bit higher than we have become accustomed to, and consumer rates, such as mortgages, staying higher as well. Covid revealed the risks of offshoring much of our production capacity. Tariffs are acting as an accelerant to the trend already in place since the pandemic. Our sense is we will reach a point where we understand we do not want every manufacturing job back in the U.S., but there are clearly some areas where better control of production and distribution—in a word, resilience—is a benefit worth paying for.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)