No funding crisis in sight—but rising US debt a concern

Total national debt still rising by the minute

The passage of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) made the tax brackets currently in force permanent and provided some additional tax breaks for individuals and corporations. The “cost” of this bill is still a matter of debate, but one thing appears almost certain: our annual budget deficits are not going lower, which means the total amount of outstanding debt we have is going higher.

As part of this bill, Congress voted to raise the debt ceiling by $5 trillion. The last time we hit the debt ceiling, Congress did not put a dollar amount on the debt ceiling, but rather set a date, January 2025, as to when we would have to revisit this issue. In effect, Congress suspended the debt ceiling for a period of time and as expected, the U.S. spent a lot more money and added to the total debt, which now totals over $36 trillion.

Since hitting the debt ceiling in January, the U.S. has continued to issue bonds and paid its bills, as the Treasury used its general account and moved money between accounts as needed. The Treasury’s general account is outside the U.S. banking system, which meant that as these monies were disbursed, this added liquidity to the banking system and the economy overall. With a higher debt ceiling in place, we can now expect a surge in Treasury issuance as the Treasury Department refills its general accounts and issues debt for already-approved spending.

In the immediate post-OBBBA days, we started to see some level of increased angst around the current and future level of the federal debt. This is not a new concern and is one we share, but there were some questions around the demand for this increased issuance now that the debt ceiling has been raised. We have written in past articles about keeping an eye on factors like the bid-cover ratio, the amount of direct bids and measures of foreign demand as we try to discern if the market is beginning to struggle with the amount of U.S. debt outstanding. To date, there are limited signs of any difficulties.

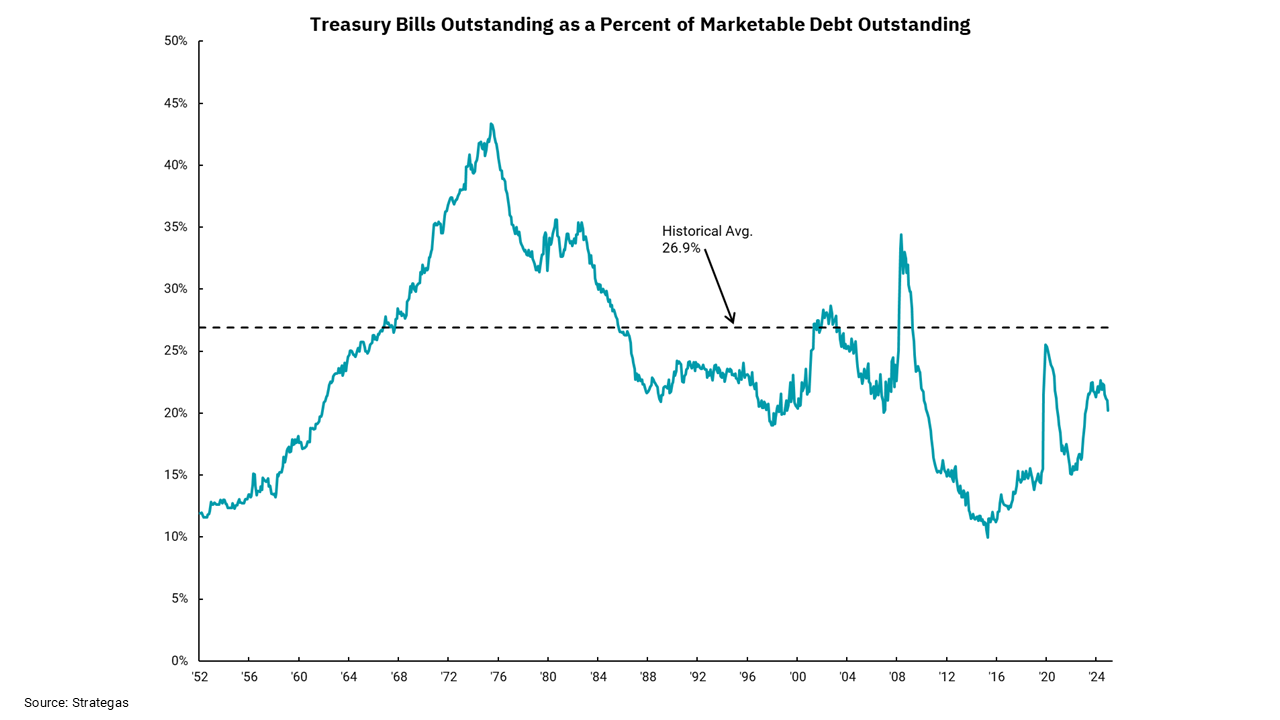

The structure of the national debt is an important part of this equation. The Treasury Department can shift the mix of short-term versus long-term issuance based on its views of where demand may lie, which can influence the cost of issuing debt. Our chart this week shows the historical amount of Treasury Bill issuance. Treasury Bills are one year or less in maturity, as a percent of overall marketable debt. Using short term debt has advantages and disadvantages. If rates are falling, this means the debt is repriced quickly and lowers overall borrowing costs. However, we have witnessed the opposite side of that equation over the last few years as the Fed had to raise rates aggressively as inflation took off. As we think about the upcoming surge in issuance, the shape of the yield curve and the outlook for lower rates might incent the Treasury to increase the amount of issuance on the short end of the curve. This also limits the amount of risk from issuing longer-term bonds when investors are skittish about overall debt levels.

Reducing the deficit is not going to get any easier from here. However, we would reiterate that there is no funding crisis in the foreseeable future.

Get By the Numbers delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe (Opens in a new tab)