Why the Fed has continued raising rates

The Fed has stayed the course in its battle against high prices, despite industry turmoil

When three banks failed in March, many speculated that the Federal Reserve would at least temporarily stop raising rates, out of concern that the rate hikes have been putting strain on the financial system.

The Fed didn’t stop.

Instead, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) hiked the Federal Funds rate by one-quarter of a percentage point in March. They then increased the rate, which also raises the cost of lending for businesses and consumers, by another quarter of a percentage point in May, reaching a range of 5% to 5.25%, before deciding to hold steady in June.

Alongside these rate increases, the Fed also has been addressing concerns that the hikes are putting pressure on some financial institutions’ liquidity—that is, these institutions’ ability to meet their obligations (such as depositors’ withdrawals) without incurring significant losses. The program that the Fed created offers loans of up to one year to banks, credit unions and other eligible depository institutions that pledge U.S. Treasuries, mortgage-backed securities and other qualifying assets as collateral.

“Certainly, it’s a lifeline for those banks that are experiencing a lot of stress,” said BOK Financial® Chief Investment Officer Brian Henderson. “As long as the Fed has rates where they are, there’s going to be stress on banks to raise deposits higher to meet where money market fund yields are.”

However, since March, lingering inflation—not turmoil in the financial system—has proved to be the most significant hurdle.

“Most banks are not under severe stress,” Henderson noted. “Use of the Federal program has not been increasing anything like at the level back in March.”

Fed dual actions have precedent in the U.S. and U.K.

The idea that central banks can ultimately continue to raise rates while also responding to liquidity issues in the banking sector has some precedent in the U.S. and, more recently, in the U.K., Henderson said.

The Bank of England had been doing quantitative tightening and hiking rates to curb inflation when, in September, a dramatic rise in interest rates on long-dated UK government bonds caused debt markets to spiral, putting pension funds under severe downward pressure.

“In response, the Bank of England had to temporarily expand its balance sheet to buy government bonds before continuing to hike rates,” Henderson said. “The Bank of England was successful because it was a short-term liquidity issue, not a solvency issue. I think that’s what the U.S. Fed also is trying to do—separate these liquidity issues from the rest of the banking industry, which is well capitalized.”

Closer to home, when the Fed first introduced quantitative easing (QE) programs in 2009, the long end of the bond market’s reaction was uncertain, so they positioned QE as separate from monetary policy addressing the rest of the economy, Henderson continued. “Of course, later as the economy continued to struggle, the Fed already had rates at 0% and the markets were concerned about the Fed’s ability to continue to stimulate the economy, then QE and monetary policy became conjoined.”

What’s next

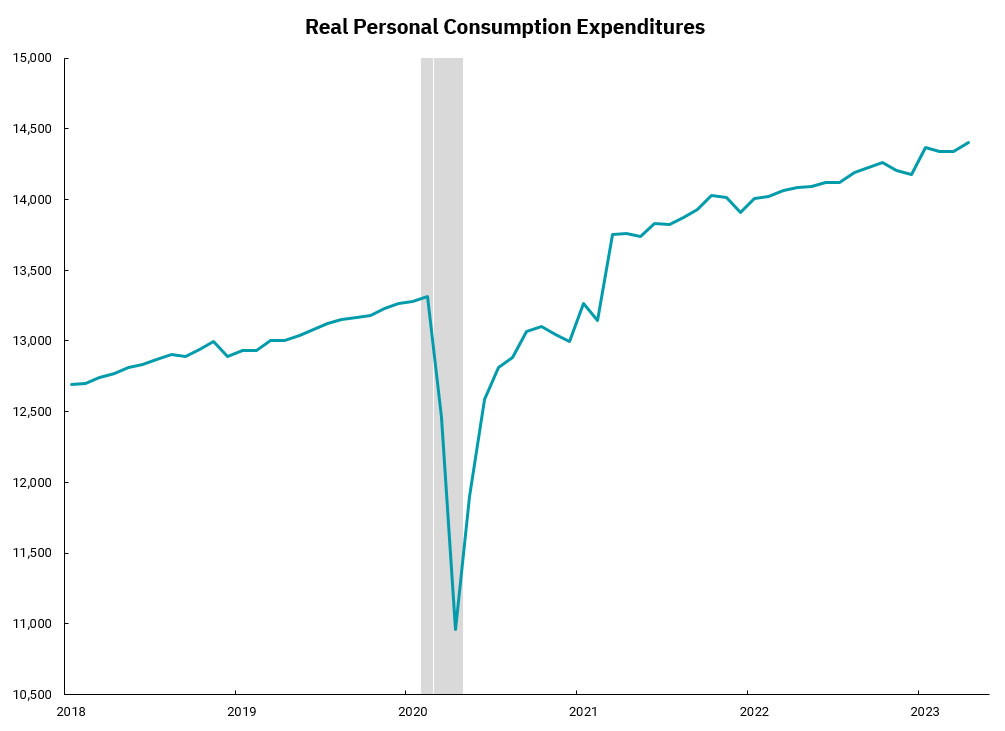

Today, despite the series of rate hikes over the past year and recent financial industry events, positive U.S. gross domestic product numbers show a still-strong economy. The unemployment rate is still low and there are still excess savings—all signs that point to U.S. consumers (and with them, the larger economy) remaining strong, Henderson said.

But that might change, he noted.

One factor is that banks are being more cautious about lending money. This tightening of lending standards started before the most recent financial industry events, but it’s happening even more now. “That’s going to also have a cooling effect on economic growth,” Henderson explained. “What I’m concerned about is that we’re on track for recession.”

If a recession does occur, the one bright side according to Henderson is: “Following every recession that we’ve ever had, the year-over-year inflation rate has always gone down—in every single one.”

2023 Midyear Outlook

BOK Financial investment experts Brian Henderson, Steve Wyett and Cavanal Hill Investment Management President Matt Stephani provide their outlook on key issues affecting the economy and financial markets for the remainder of the year.