Will the Fed still be able to cut rates in 2024?

High costs of car insurance and rent among the factors keeping inflation up

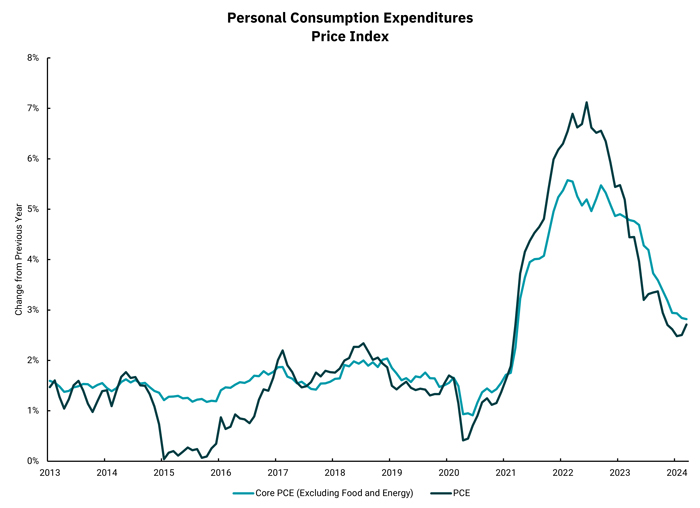

When 2024 began, markets were pricing in six rate cuts. In just a few months, that figure has dropped to roughly two cuts—and even that is questionable, especially after the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE) increased 3.4% year-over-year in the first quarter, nearly double the pace of inflation growth in the fourth quarter of 2023.

Most recently, on Wednesday, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced that it would continue holding the Federal Funds rate at a range of 5.25% to 5.5%. Explaining its decision, the committee said that it "does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2%."

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell elaborated on this point further in the post-meeting press conference. "I don't know how long it will take. I can just say that when we get that confidence, then rate cuts will be in scope—and I don't know exactly when that will be," he said.

He also addressed the question of whether the Fed's next move will be a rate hike, a scenario posited by some investors, and said that it's "unlikely."

Now many investors aren't anticipating the first rate cut to come until November or, at the earliest, September.

Rates likely to stay higher for longer

Although keeping the Fed Funds rate at this level isn't as restrictive to the economy as another rate hike would be, this "higher-for-longer" strategy does have its impacts on consumers and businesses, especially after the U.S. economy grew by its slowest pace in nearly two years during the first quarter of 2024, said BOK Financial® Chief Investment Officer Brian Henderson. The Fed Funds rate is the overnight interest rate that banks charge each other to borrow money, and the interest rates charged to consumers and businesses on debt tends to go up and down in relation to it.

"The economy is still very strong. However, the longer these high interest rates last, the more sectors of the economy will feel that pinch and the more corporate debt will come due and have to be rolled over at these higher rates," Henderson said.

When companies' debt expenses increase, that impacts earnings and company leaders may start cutting expenses in other ways, such as by laying off employees. That, in turn, could lead to higher unemployment, lower consumer confidence and less spending, especially on big-ticket items such as cars and luxuries such as entertainment, he continued.

Recession still unlikely

Still, Henderson doesn't think a recession will happen, especially given that the U.S. is in an election year. Although the Fed itself is apolitical, meaning that its monetary policy decisions should not be influenced by politics, decisions made by Congress and the president impact economic growth and inflation.

For example, President Biden may authorize the release of Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) oil to lower gas prices in response to geopolitical tension in the Middle East, Henderson noted. Although energy prices are not part of "core" inflation, which is the measure of inflation preferred by the Fed, they are part of overall inflation and, moreover, they tend to drive campaign rhetoric.

'Shadows of the pandemic' still being felt

But much of inflation's persistence has less to do with current politics, whether at home or abroad, and more to do with structural issues, some of which can be traced to the pandemic, Henderson noted. "We're still living through some of the repercussions, " he said.

For example, the cost of car insurance has increased more than 20% in the last 12 months due to insurance companies having to "catch up" to the rising costs of claims. One factor driving these claims costs is the higher price of new cars, caused by greater demand for cars during the pandemic (possibly due to people receiving stimulus checks) and supply chain issues. Henderson expects car insurance premiums to rise at a slower rate as car prices come down. However, disinflation—that is, car insurance premiums dropping in price—probably won't happen , he said.

Another structural issue is the lack of supply of homes. Although more multifamily homes have been built, there's still a shortage of 7.2 million single-family homes, relative to the number of household formations, according to a Realtor.com report. Meanwhile, renters have been dealing with rent prices that are now 30% higher than they were before the pandemic. The good news is that the pace of rent increases seems to be slowing somewhat, but the fact that rents are already so high to start means that many renters will still be feeling the pinch.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Should the Fed adjust its target?

In the meantime, the last leg of the road to 2% inflation has proved to be the rockiest, compared to the easier declines in inflation from its 9.1% peak in June 2022 to its current rates of around 2.5% to 3.5%. (In March, CPI increased 3.5% year-over-year and PCE increased 2.7% year-over-year. Core CPI, which excludes food and energy prices, increased 3.8% and core PCE increased 2.8%.)

In response, there has been some talk that the Fed should reconsider its 2% target for inflation, which was officially set by the Fed itself in 2012.

But that would be a mistake, Henderson said.

"If the Fed were to waver even a little bit from that commitment to 2% inflation, then inflation expectations would rise and it would increase the probability of a second 'echo wave' of inflation," he said. "Instead, using communication that's reassuring and supports confidence in financial markets will help the Fed achieve its 2% goal."