The changing face of the US worker

As more Baby Boomers retire, who will fill the demand for labor?

America is aging and it may have serious ramifications for the job market.

“Labor force participation rates started to rise in the mid-'60s when the Baby Boomer generation entered the workforce. Then, in the late '90s, the late Baby Boomers started retiring and that has been continuing ever since, dwindling the number of eligible workers,” said BOK Financial® Chief Investment Officer Brian Henderson.

Over the next six years, employers may have to replace between 10.8 million and 14.8 million employees who are “Peak Boomers”—that is, people who will reach the peak retirement age of 65 between now and 2030.

This potential surge in retirees comes after the COVID pandemic already accelerated the pace of Baby Boomer retirement. In 2020 alone, the most recent year for which there was data available, there was a 3.2 million increase in Baby Boomer retirees, compared to only a 1.5 million increase in 2019, according to the Pew Research Center.

Will there be another worker shortage?

Baby Boomers taking early retirement was one of the factors that contributed to the worker shortage after the pandemic, which was so severe that there were two open positions for every person seeking work in 2022. Other reasons for the worker shortage included people fearing exposure to COVID, families facing childcare issues and a reduction in immigration during the pandemic, Henderson explained.

Since then, the ratio of open jobs to unemployed persons has been trending down. However, as more Baby Boomers retire, that could change—if there aren’t enough workers to fill the dwindling supply, Henderson said.

One potential source of new workers is immigration, he continued. For instance, the more open immigration policy after the pandemic has increased the number of workers available, especially for service positions in leisure and hospitality. “They’ve also helped contribute to economic growth through more consumer spending and increased the demand for housing,” he explained.

Meanwhile, the rising number of remote and hybrid positions is also helping to increase the supply of workers in the labor market because the flexibility is enabling people to work who might not otherwise be able to, Henderson said.

"With remote work, the quality of work-life balance has increased for some,” Henderson explained. “Childcare was difficult to obtain after the pandemic and, even now, remote work tends to help the primary childcare provider the most.”

Workforce becoming more diverse and educated

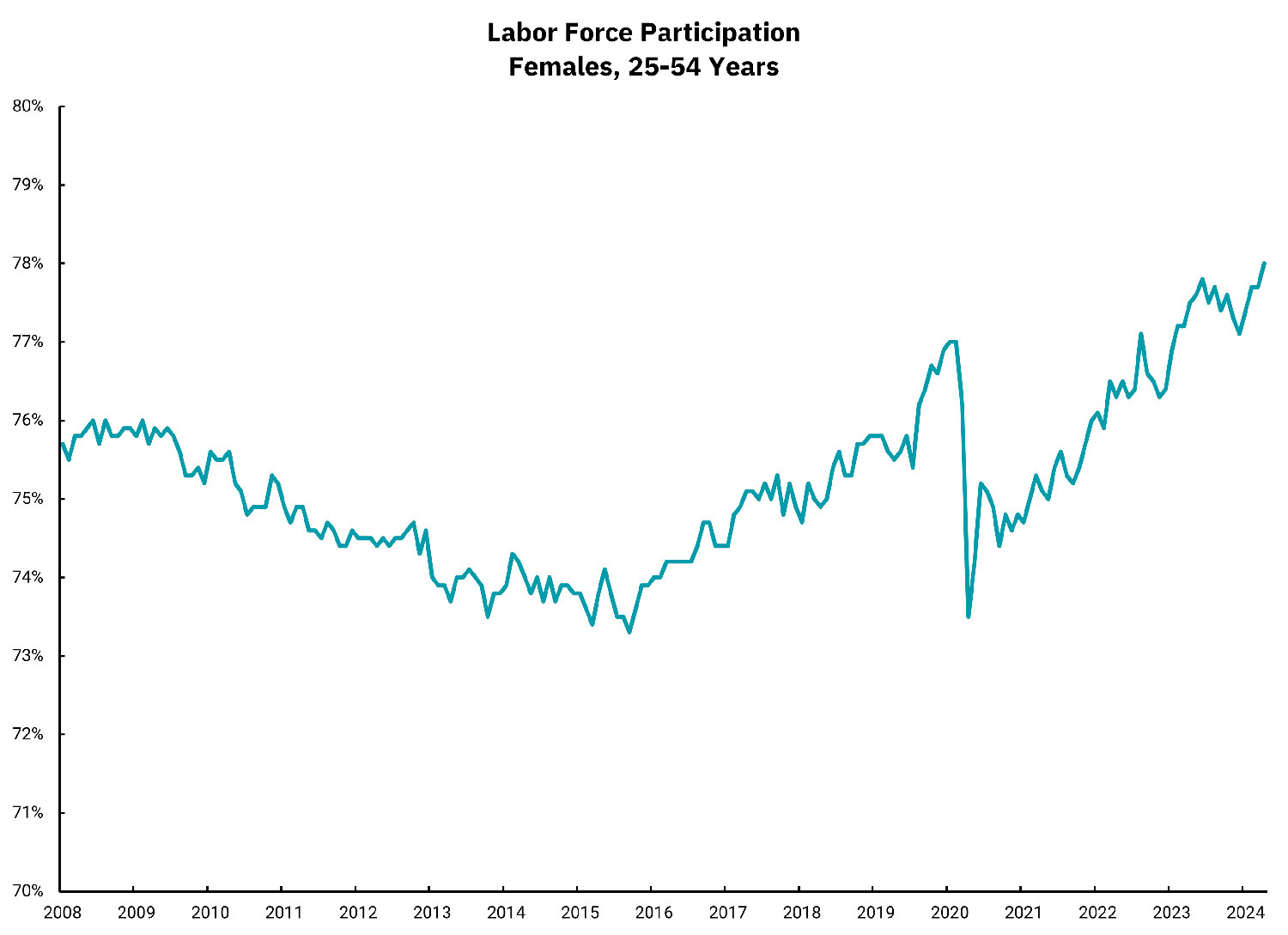

Since women tend to take on more childcare responsibilities than men, according to some studies, the increase in remote work opportunities may have helped more women in particular enter the workforce. In fact, the percent of women aged 25-54 in the workforce has risen to record levels—at 78.1%, as of May 2024, according to St. Louis Fed data.

However, the record number of prime-age women in the workforce also continues pre-pandemic trends. First, rising costs have made many families unable to live on one income alone and, second, more women—and men—have been going to college, resulting in a more diverse and more educated workforce, Henderson continued. As of 2021, 37.9% of people in the U.S. aged 25 and older had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. By comparison, in 2000, that figure was 24%.

Workers with and without college degrees in demand

Today, those with a bachelor’s degree have an extremely low unemployment rate—at only 2.4%, as of June 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. However, this figure just means that they have a job—not necessarily that they have a job in line with their education level. They may be “underemployed,” meaning that they are working at jobs that don’t require a college degree.

Yet it’s not just college-educated workers who are experiencing the benefits of the still-tight labor market. The unemployment rate for those with just a high school diploma was 4.2%, as of June. “The fact that this figure is so low shows the receptiveness of the job market to people who don’t want to incur student debt or don’t want to pursue college for other reasons,” Henderson noted.

Meanwhile, June’s overall unemployment rate of 4.1% was also surprisingly low, given how much the Fed raised rates in this cycle and how quickly they’ve done so, Henderson said. Moreover, for 27 consecutive weeks leading up to May, unemployment was less than 4%, a duration of sub-4% unemployment not seen since the 1960s.

But low unemployment came at a cost back then, Henderson warned.

“There was a new economic model that had really captivated policymakers called the Phillips Curve. This model created some hubris in which economic policymakers felt like they could run the economy a lot faster than they really could,” he explained. “This approach has been debunked since then, but it set the stage for the stop-go central bank policy and the high inflation that started in the ‘70s.”

It's this stop-and-go approach that the Fed is trying to avoid now, which has led them to take a higher-for-longer approach to rates. However, even after one of the most aggressive rate-hiking cycles the U.S. has ever seen, unemployment has remained low.

All of that said, when unemployment does rise, it may rise rapidly, Henderson added.

“The Fed doesn't have a great track record on hiking just enough. In fact, in most periods, they’ve hiked too much and, once the unemployment rate starts moving up, it tends to spike up.”- Brian Henderson, chief investment officer at BOK Financial

The future face of the U.S. worker

Looking forward, experts predict that the American workforce will continue to grow more diverse and educated—but that some types of jobs may disappear while other fields grow. For example, as a result of deglobalization, more manufacturing will return to the U.S., as U.S.-based companies move production away from countries like China and to the U.S. and Mexico. Some legislation has been positive for American manufacturing as well. The CHIPS Act, for example, has increased the need for construction workers to build semiconductor plants in the U.S. and also for workers to work in those plants, Henderson noted.

However, at the same time, developments in robotics and automation may mean that some manufacturing jobs will be replaced by robots. An Oxford Economics report predicts that 20 million manufacturing jobs will be displaced by robotics by the year 2030, meaning that 8.5% of the global manufacturing workforce stands to be replaced.

In other fields, too, the types of jobs may change, with some jobs going away and others being added, but the overall increase in productivity that AI and other technology is expected to bring will benefit everyone, Henderson said.

“Companies will have to create new types of jobs that we don’t even know about right now—people who are specialists in the new technology,” he said.

Now decides the future

View the interactive video, a downloadable report and other articles prepared by the BOK Financial investment management team.