Can the U.S. grow its way out of its ‘debt trap’?

Even just a 0.5% increase in economic growth per year could dramatically reduce the rise in federal debt

To most Americans, the national debt is a number that they’re aware of and can possibly ballpark guess—but, for the most part, it seems like an abstract and distant concern.

To some extent, they’re right.

“As we sit here today, the national debt is not posing any kind of a risk to the U.S. economy or the U.S. as a whole,” said BOK Financial® Chief Investment Strategist Steve Wyett. “The Treasury can sell all the Treasuries that it needs to fund the deficit. It also doesn't appear that we're paying a materially higher interest rate on the debt, except what’s being driven by monetary policy.”

But here’s the problem: “The annual budget deficits that the U.S. government is running are not sustainable over a long period of time. It's hard to know when that tipping point will be,” Wyett said.

In other words, the national debt—which totaled more than $36 trillion, as of late November—isn’t a pressing problem right now, but someday it will be, and no one knows exactly when.

And in the meantime, the more the federal government is spending on interest costs on that debt, the less flexibility there is in the budget to spend on other things, noted BOK Financial Chief Investment Officer Brian Henderson.

“At some point, the U.S. will have a recession and will need the ability to cut taxes and increase government spending to stimulate growth. Those options could be more challenging if the debt levels get too high.”- Brian Henderson, BOK Financial Chief Investment Officer

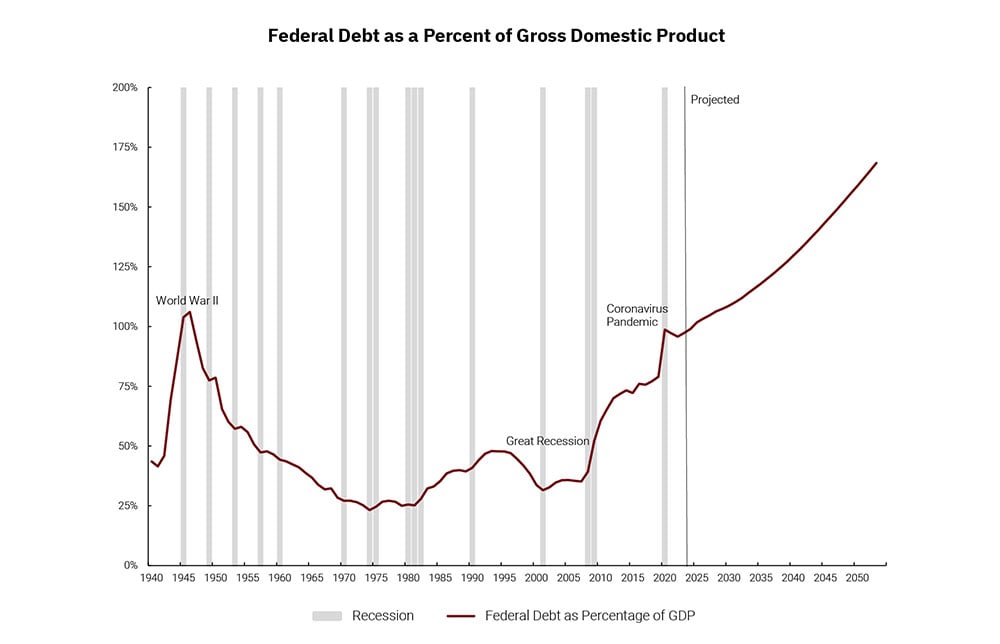

In fact, President-elect Trump’s proposals to lower the corporate tax rate to 15% and extend the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) provisions might be more difficult to accomplish because of the enormous deficits that the federal government is running relative to the size of the economy, Henderson said. Debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) levels are now higher than at any time in U.S. history except during the height of World War II, according to figures from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

The national debt situation today

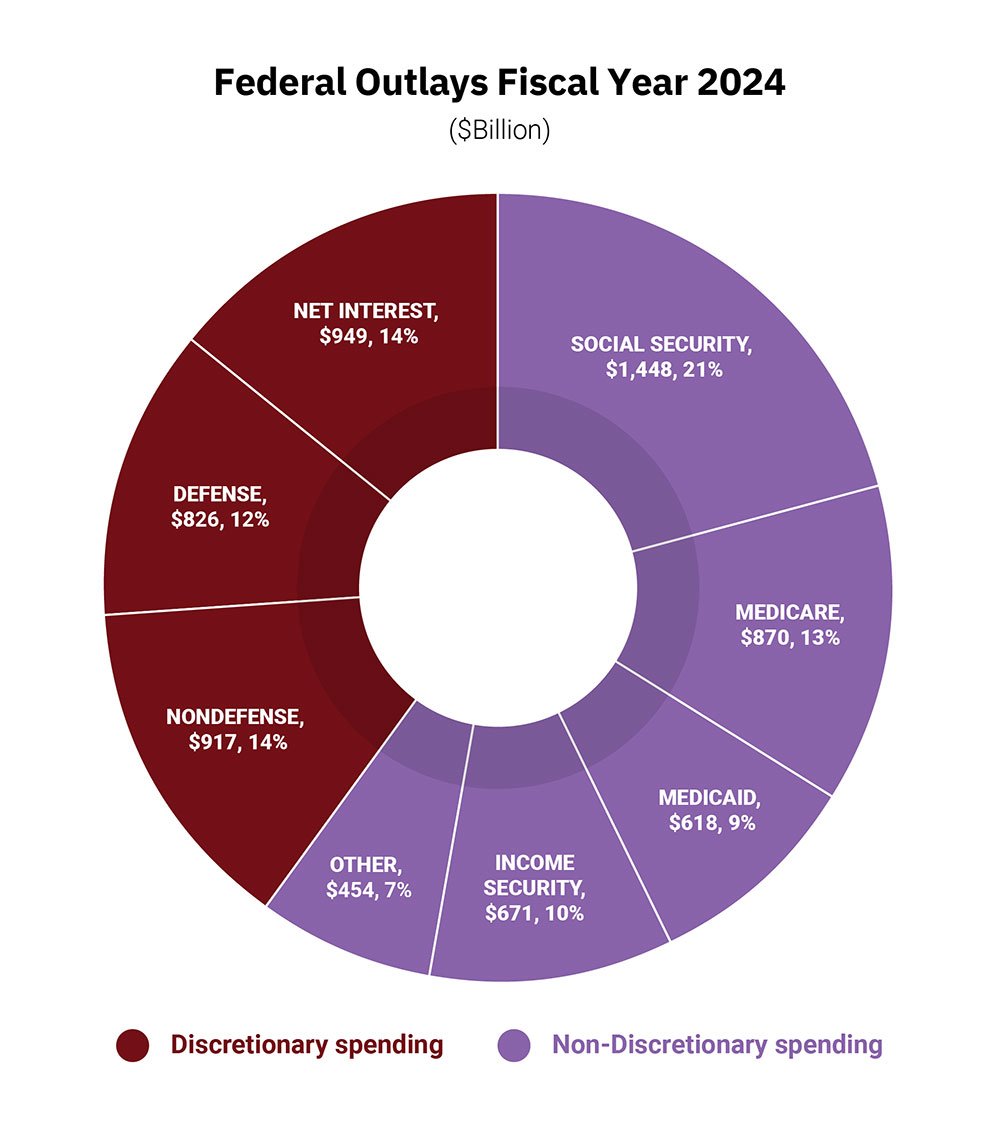

In 2024, the federal government’s budgeted interest rate costs exceeded the amount budgeted for defense spending for the first time ever—at around $950 billion for net interest costs versus $826 billion for defense spending. That was partly due to the fact that the U.S. government, like everyone else with debt, has to pay higher debt servicing costs when the Federal Reserve raises rates.

Source: Congressional Budget Office. Data as of Sep. 30, 2024

Source: Congressional Budget Office. Data as of Sep. 30, 2024

As the Fed continues to cut rates, as it’s expected to do in 2025, interest rates charged on short-term debt will fall as well. However, as anyone with a large amount of debt knows, incremental drops in interest rates don’t change the bigger issue—that you have a massive amount of debt that’s accruing interest.

Potentially worsening the problem is the possibility that, if the U.S. imposes broad or high tariffs, there could be less foreign interest in buying U.S. Treasuries, which could exacerbate the U.S.’s federal debt crisis, Wyett noted.

“A lot of foreign governments buy U.S. Treasuries because we run a trade deficit,” he explained. “Exporters into the U.S. inevitably have dollars that they need to recirculate, and some of those make their way into buying Treasuries.

“As we deglobalize, as we're having less imports coming into the United States, then those foreign governments have fewer dollars to recirculate into the U.S. Treasury, so we're probably going to see the amount of foreign buying decline for no other reason other than that they’re just not doing as much business with the United States.”

The path forward

Experts don’t believe a balanced budget is a likely scenario in the near- or far-term; instead, the more likely path is a slow decline in the size of the annual deficit. “We need some sort of a plan to help the 6-to-7% annual budget deficits that we’re running now become 5%, 4%, 3% and 2%—something a little more sustainable,” Wyett said.

The question is how to get there, and experts say there are three potential paths ahead—1) austerity, 2) growing the economy through inflation or 3) growing the economy through increases in productivity and/or more workers. Only the last of the three paths will likely be palatable to American consumers, businesses and politicians, experts noted.

“Austerity would likely mean a combination of tax increases and spending cuts, which could be very painful for many Americans,” Wyett said. For instance, these spending cuts could include a reduction in social benefit programs, which might increase homelessness in the U.S.,” he said.

Another option is for the U.S. government to “inflate its way” out of debt, said Matt Stephani, president of Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc., a subsidiary of BOKF, NA. A budget model constructed by the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School projected that permanently increasing the Fed’s current 2% annual inflation target to 3% would reduce the inflation-adjusted value of the federal debt by 7% by 2051, without having to lower Social Security benefits.

“But people really don’t like inflation,” Stephani noted. In fact, 41% of Americans polled by Gallup named inflation as the most important financial problem facing their family in 2024. “And so, that just leaves growing our way out of the debt problem,” Stephani continued.

How the U.S. can grow out of debt

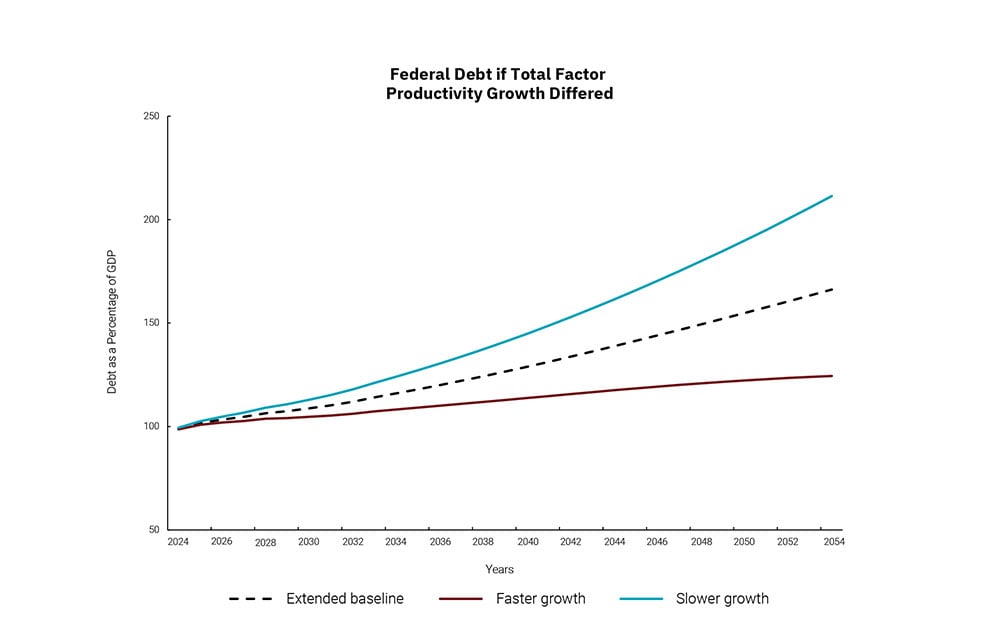

The good news is that even just small increases in economic growth can dramatically improve the federal government's debt-to-GDP levels over time, experts noted. For instance, if economic productivity were to grow by even just 0.5% more quickly than what the CBO expects, federal debt would be 124% of GDP in 2054, instead of the extended baseline of 166%, according to CBO projections.

The question is how to achieve that economic growth. One way is by having more workers in the economy, but that may be difficult due to the number of Baby Boomers who are retiring, declining population growth and proposed tighter immigration controls, Henderson said.

To build the labor force through immigration, the U.S. needs a policy somewhere in the middle, between the extremes of an open border and a hardline anti-immigration stance, Wyett said.

Another option is through anticipated increases in productivity from artificial intelligence (AI), which Stephani said could amount to another major wave of productivity in the U.S.

However, advanced AI is anticipated to require massive amounts of energy, which means that the U.S. needs energy policies that provide access to cheap, reliable sources of power, he said.

Nevertheless, it will probably take a combination of both an increase in workers and an increase in AI-driven productivity to make a dent in the U.S.’s debt-to-GDP levels, experts agreed.

“I believe we can do both. We can grow our labor force through a smart immigration policy, and we can grow our productivity through AI—and that will get us out of this debt trap that the rate of spending by the U.S. government creates.”- Matt Stephani, president of Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc.

2025 Outlook

A new year is often associated with transformation. Even so, the degree of change ahead in 2025 looks unusually large for the U.S., with potential shifts in trade policy, immigration, regulation and more. BOK Financial's investment management team has prepared its 2025 market outlook as a downloadable report, supplemental articles and a recorded webinar.